What a Long Strange Guilt Trip It’s Been

My life at age 42 is not what I’d imagined at age 18. As a teenager, I hadn’t been to South Carolina, much less thought of living and raising a family there. I grew up attending a Pentecostal church with gifts of the spirit and everyone-on-their-own-out-loud-all-at-once prayer sessions. Now, I attend a small country Methodist church with prescribed liturgical readings and recited-in-unison creeds.

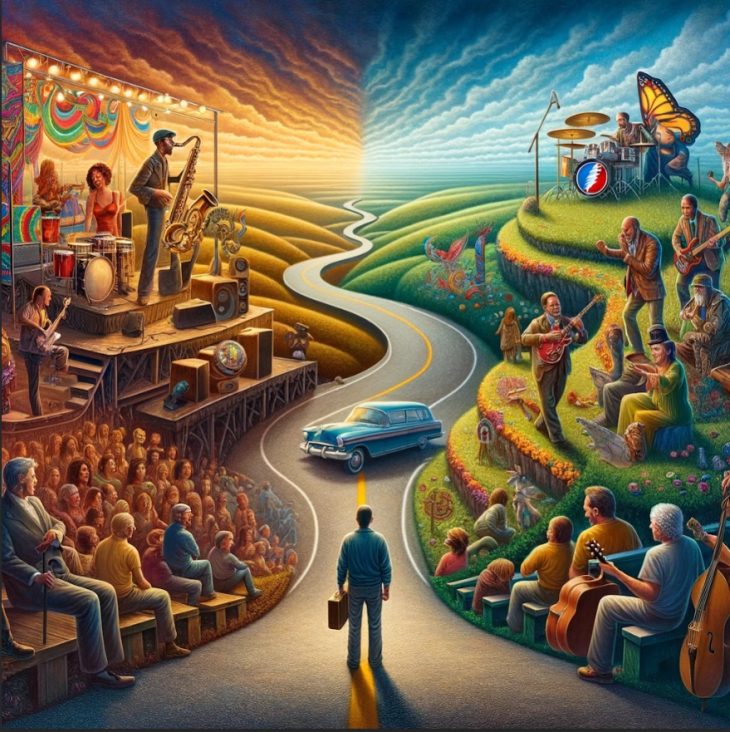

And, of course, since I loved music, I imagined seeing my favorite bands in concert with my future spouse. But could I have foreseen that I would celebrate my wedding anniversary in the year of our Lord 2023 by running at breakneck speed from a Charlotte parking lot so I could catch a performance by The Dead and Co., the most successful of the Grateful Dead spinoff bands?

In high school, I thought The Grateful Dead only had two things going against them: the condemnation of everyone whose music taste I respected and the fact that they weren’t any good. Other than that, there was a lot to love. Who cared if they were morally objectionable? They were aesthetically repellent, a guilty pleasure at best and aural torture at worst.

I was a music snob as soon as I learned about alternative and indie rock. I subscribed to a Harvey Dent-esque dictum about music allegiance: you either die a Pavement fan or live long enough to see yourself become a devotee of Phish, a grim fate indeed. Jam band fandom was where good taste went to die. I guess the Blues Travelers frontman was a pretty good harmonica player, but that was like saying you made delicious candy corn, which is to say it was losing disguised as winning. Even if the Dead were further upstream, and thus more authentic, than the H.O.R.D.E. of jam bands making the rounds when I was a teenager, this only made them somehow more responsible for bands like Widespread Panic.

As I got older, the barbs leveled against the Dead became more pointed. “No wonder their fans take all those drugs,” said the Replacements-loving wag in my life. “You’d have to be high for that music to sound good!” When I tried to listen to “Sugar Magnolia” with the ears of an instrumentalist, all I heard was noodling. When I tried to listen to the lyrics of “Touch of Grey,” things were a bit better, but I couldn’t get past Jerry’s pitchy warbling. As a young man, I’d grown up on 80s CCM, so I was no stranger to poor production marring well-written songs. I knew you didn’t have to be a technically sound singer to be great (cf. Bob Dylan). Still, when the few Deadheads I knew kept insisting that I couldn’t judge the Dead by the studio tracks I heard on classic rock radio or, if I happened to hear a live track and disapprove, that I’d just been listening to the wrong one, it was hard for the whole thing not to feel like a shell game.

But that was just one front on which the Dead got attacked.

The more severe criticism came from Christians who gave the band (and their fans) a lot of flak for being drugged-out, dissolute hedonists. While I was in high school and college, it was true that the Venn diagram of people I knew who a) regularly burned down and b) would identify as Deadheads were nearly overlapping circles. It was tough to tell if these fans had chosen the Dead as a prerequisite to the kind of lifestyle they aspired to, akin to a pre-med undergrad taking the obligatory organic chem course, or because they actually liked the music. At a certain point, however, the distinction was moot. The only Christians I heard talk about the Dead were the ones who expressed thanksgiving for being rescued from liking that kind of music and its attendant scene, and if you told me you were into “Dark Star,” you were implicitly telling me you didn’t serve the Daystar.

The irony was that I already exhibited traits that marked me as a future Deadhead. I instinctively believed that a song was better just because it was longer. It’s why I was in the bag for jazz once I discovered that hard bop and modal jazz classics like Blue Train and Kind of Blue had no tracks shorter than five minutes. Call it the Anti-Ramones philosophy of song duration. I figured longer songs meant you were getting more bang for your buck.

Add to that the fact that my charismatic upbringing left me used to a form of spirit-filled musical improvisation: a worship chorus that might last fifteen minutes instead of three, a tongues-in-interpretation moment where a song would suddenly stop and the congregation shut up on queue without a signal as we waited for God to speak, and two to three-hour church services on a Sunday night. There was a reason the form of Dead shows resonated with me when I finally got around to listening to them.

Finally, I was a saxophone player at our church who helped add a little alto and soprano spice to the typical piano/guitar/bass/drums of our worship band. So on any given Sunday night when we found ourselves, unexpectedly, in an eight-minute version of the chorus “Jehovah Jireh,” I was not just a congregation member singing the same four-line chorus twenty times. I was on the platform playing along and figuring out how to listen to where the fiery song leader (often my dad) or our pastor (a fantastic guitar player) was headed. That is, I hadn’t just listened to spirit-filled jam sessions. I’d been playing in the band. And, on a few special nights, my horn was the proximate cause for the move of the Spirit.

But I can only see those inchoate traits in retrospect. I was too busy listening to Pavement’s Slanted and Enchanted, Son Volt’s Trace, Jeff Buckley’s Grace, and The Sundays’s Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic to get anywhere near Live/Dead or Europe ‘72.

I got to be a Dead fan like Mike Campbell from The Sun Also Rises went bankrupt: gradually, then suddenly.

I really loved the 2005 Ryan Adams albums Cold Roses and Jacksonville City Nights, both indebted to the rootsy Americana of Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, especially when Adams and his band The Cardinals played the songs live. When my wife shared her fave all-time songs, her disc began with “Scarlet Begonias,” a song I’d never heard before. Its syncopated rhythms, fantastic solo and outro, and evocative story–it was by far the best Dead tune I’d ever heard. There was Bert, my first honest-to-goodness tie-dyed-in-the-wool Deadhead friend, who had seen over 100+ shows of the original band and at least as many concerts of the spin-off incarnations. I loved hearing stories about the scene surrounding the Dead, and when I’d hear a new Dead tune I dug (“Stella Blue” or “Cosmic Charlie” or “Wharf Rat”), I’d ask him questions about lyrics or the best versions of the song he’d seen live.

And then, just as Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home doc spurred my love for Dylan, the multi-part 2017 film Long Strange Trip also provoked my Dead deep-dive. As a teen, the closest I’d gotten to a Grateful Dead doc was the Kris-Kristofferson narrated VH1 Legends episode, which bordered on parody in its use of the story tropes of artistic creativity, chemical addiction, inter-band squabbling, and untimely death. LST not only filled in a lot of the band’s history I didn’t know, but it also came with a playlist that introduced me to many songs (in their live incarnations!) that I’d never heard.

That was it. I was in. And so, I’ve gone through all the band’s eras over the past six years. The late 60s experimental stuff with Pigpen. The Europe ‘72 concerts. All the Betty-board 1977 shows.The early Brent Mydland years. Jerry right before and after his pre-diabetic coma, wherein, as Bert told me, his singing voice bore an uncanny resemblance to Big Bird.

The COVID-era lockdowns gave me a lot of time to listen to whole shows and hear what each band member brought to the band. I knew I was in for real when I could wax poetic for two minutes on Bob Weir’s rhythm guitar playing or the counterpoint basslines Phil Lesh added to a particular song. Plus, the music is excellent for playing in the kitchen while my wife or I make dinner. If we’ve got forty-five minutes, that’s time for at least three songs, right?

Along the way, I’ve picked up things from the band that reinforce things I already knew from my faith.

Most importantly, judging the music by the fans is a bad idea. It’s a cliche about how many people have been turned off to Christ because of Christians. And I know I’ve been the Christian who shakes his head when a prominent celebrity preacher uses the name of Christ to justify get-rich-quick nonsense or warmed-over left-over self-help practices, much less to hide moral degeneracy. Deadhead fans aren’t blind to the people who are just into the Dead because the scene’s heavy on hallucinogens. Real fans like my friend Bert care about the music, and if I didn’t love “Help on the Way,” the fans wouldn’t be much help anyway.

Plus, the Dead’s catalog is a constant reminder that you’re only one listen away from hearing a song in a new way for the first time. I’m sure you’ve read particular passages of scripture multiple times only to have your 351st time through it hit you like the atom bomb. “Oh! That’s what makes the discussion of the sheep and goats so devastating!” or “I’d never noticed the context for that suitable-for-a-Hobby-Lobby-piece-of-wall-art verse in Jeremiah before!” Because so much of the Dead’s live work is available for streaming, you can hear the same song again and again and again during a tour or across tours. So there are different incarnations of “St. Stephen” or “The Other One” or “Scarlet Begonias/Fire on the Mountain” (dig this one that puts “Touch of Grey” in between the two). I skipped “Loser” or “Not Fade Away” or “Let It Grow” or “Birdsong” in live sets for the first four years of my fandom, and now those songs are some of my favorites.

And that’s because the most important thing you can do as a fan of the Dead, or as a follower of Christ, is keep listening. There’s a reason why the repeated refrain from Revelation is, “He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says…” The band’s superpower was the willingness each of its members had to listen to each other. Jerry was the only true instrumental virtuoso in the group. Still, he wouldn’t have gotten where he went without collaborators: Robert Hunter’s lyrics or the musical partnerships offered by the band. Dennis McNally’s band bio makes that clear. I’m still unsure what Mickey Hart is doing up there, but I don’t always know why I need to listen to Leviticus or particular parts of Ezekiel, either.

So what happened when my fandom took me and my wife to a Dead and Co. show in May? A whole lot of people watching, but frankly, it wasn’t all that different from the mega-rallies I used to attend on Friday nights. More charismatic resonance, I suppose.

I discovered that while I probably know more than 99% of the world about the Grateful Dead, I wasn’t even in the 25th percentile of those fans. I hadn’t heard “Loose Lucy” before, and I didn’t know “The Wheel” at all, yet countless people–young and old–sang along to every lyric. There’s a set of people who’ve gotten into the band due to John Mayer’s collaboration with Bob Weir, and there are people who you just know saw the band back in 1971.

I also left that night knowing I’m not an unadulterated fan. No one else ran in a dead sprint to get to the show; the Deadhead tribe is more of a loping crew. I wasn’t in official Deadhead garb and stayed stone-cold sober for the entire show. And it’s tough to tell how many people around me singing “Fire on the Mountain” would have joined me in a full-on-belief-filled rendition of “Go Tell It on the Mountain.”

But I keep listening with a guilt-free conscience. To paraphrase the great Robert Hunter, if a man among you’s got no sin upon his hands, let him cast a stone at me for listening to the band.