Word of the Day: Carl

Today’s word of the day is carl. According to www.dictionary.com, a carl is a strong, robust fellow, especially a strong manual laborer; a miser or an extremely thrifty person. It used to mean a churl or a bondman, though the latter two definitions are obsolete. Then again, apart from using the noun as a proper noun (as someone’s name), nobody really uses the word carl anymore. According to www.etymonline.com, the word entered the English language “c. 1300, ‘bondsman; common man, man of low birth,’ from Old Norse karl ‘man (as opposed to ‘woman’), male, freeman,’ from Proto-Germanic *karlon- (source also of Dutch karel ‘a fellow,’ Old High German karl ‘a man, husband’), the same base that produced Old English ceorl ‘man of low degree’ (see churl) and the masc. proper name Carl.

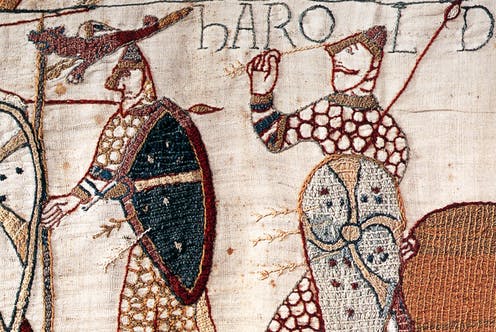

On this date in 1066, the most important event in the history of English language took place: the battle of Hastings.

Some background. What we today call the United Kingdom, or the British Isles, was once ruled by Celts, people who spoke a far different language than English. The main body of Celts, the Britains, were for a time ruled by the Romans, who helped the Celts fight off incursions by the Scots and Picts, tribes that lived in what we call today Scotland. Evidence of the Romans’ assistance includes Hadrian’s Wall, begun in 122 A.D. and Antonine’s Wall, begun in 142 A.D. Both cut across the width of England to separate it from Scotland, from the Picts and Scots, with the Antonine Wall being somewhat further north. The Romans were in Britain from the middle of the first century A.D. until the early part of the fifth century. Then, as the Empire began to collapse, the Romans left Britain to the British.

The story is that King Vortigern, the King of the Britains, while struggling on his own to keep of the Picts and Scots, invited two brothers, Hengist and Horsa, from what is today northern Germany, to help him fight off the Scots. With the two brothers came mercenary soldiers from the Saxons, the Angles, and the Jutes. But the Germans, whom we refer to today as the Anglo-Saxons, decided they wanted the land for themselves, and the drove the Britains out of England.

A lot of stuff happens in the next 550 years or so, including invasions by the Danes, but ultimately the Anglo-Saxons control most of England. In the early eleventh century, the Anglo-Saxon king was Æþelræd II (Athelred). Æþelræd is usually referred to in history as Æþelræd the Unready, but his real nickname came from the Anglo-Saxon word unræd, meaning “poorly advised,” which was a pun on his name, which meant “well advised.” But whether from a lack of readiness or poor advice, Æþelræd was troubled by invasions from the Danes. He paid tribute to the Danes after losing the Battle of Maldon in 991 (there’s a famous Anglo-Saxon poem about this battle), and then he was driven from England by Sveyn Forkbear in 1013. He returned as king the next year, after Sveyn’s death, but after his death and the death of his son, Sveyn’s son, Cnut, became king.

Another of Æþelræd’s sons, Edward, would eventually become the king in 1042, but not until after spending 25 years or so in exile in Normandy. During that time, Cnut was both king of Denmark and England, followed by his brother, Harthacnut, who was more concerned with maintaining his power in Denmark. So Harold Harefoot was made regent of England in 1035. Edward returned from exile in 1036, along with his brother Alfred. Alfred was captured by Godwin, Earl of Wessex, and handed over to Harold Harefoot, who basically murdered him. This result instilled in Edward a hatred for Harold and for Godwin.

In 1051, when Edward the Confessor was king, William of Normandy visited him. Later, according to William, Edward told him that, since Edward had no children, he wanted William to succeed him as King of England. But when Edward died in January of 1066, the Witenaġemot (the meeting of the wise; really, the meeting of the ruling class of England) chose the son of Godwin, Harold, to be the next king. But Harold Godwinson faced two problems at the beginning of his reign.

The first problem was his brother Tostig, who allied himself with a Norwegian named Harald Sigurdsson, though usually called Harald Hardrada (“hard council” or “hard ruler”). Tostig invited Harald to take the English throne for himself, and Harald and Tostig, with an army, invaded England in September of 1066. After initially defeating an English army at the Battle of Fulford on September 20, 1066. But just five days later, Harald and Tostig met the army of Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, and Harald and Tostig were soundly defeated, and both of them died.

But then Harold had to deal with his second problem, the claim of William of Normandy. William’s claim was actually not legitimate because the Anglo-Saxon system was not truly a hereditary monarchy—the moot was supposed to declare the next king, and it had done so. But William came anyway. Harold Godwinson and his army had to march from Stamford Bridge, 185 miles north of London, to Hastings, south of London. The march was over 250 miles. Exhausted and depleted by the march, the Anglo-Saxons lost to William from Normandy, and the course of our language was changed forever.

William and his followers spoke a version of French, called Norman French. So the new aristocracy of England spoke a version of French while most of the workers, the peasants, spoke Anglo-Saxon, or Old English. Over the course of the next 300 years, these two languages became a creole (a creole is a pidgin language that becomes the primary language of a speech community, and a pidgin is a language that is a blending of two languages, with a simplifying of the grammar and wide variety of pronunciation). This creolization of English resulted in a simpler grammar than is evident in either Anglo-Saxon or Norman French, as well as a duplication of words.

William was a carl; nay, he was a churl. He had no right to the English throne. But the truth is, probably, that Harald Hardrada and Harold Godwinson were probably churls as well, along with Tostig, Edward the Confessor, Æþelræd, Sveyn, and most of the others. They were, for the most part, strong and robust men, good in battle. But they were also willing to kill other people and let other people die in order to obtain what they wanted. But as bad a carl as William of Normandy was, the silver lining to the cloud that was the Battle of Hastings was the development of the language that we speak today.

The image is from the Bayeux Tapestry, a 230-foot long tapestry that tells the story, from the Norman side, of the events leading up to the Battle of Hastings as well as the battle itself. This small part shows Harold Godwinson, King of the Anglo-Saxons, with an arrow in his eye. Harold died early on in the battle, perhaps from a lucky Norman arrow, and William became king.