Talk Is Easy. Love Is Hard.

Easy A (2010) boasts a witty script and a boffo performance from its lead, Emma Stone. Since Stone’s character Olive dominates the film’s lines and camera lens, director Will Gluck is sitting pretty. Every scene with Olive’s family is a hoot (Tucci, who plays Olive’s dad, is comedic gold), and at just over 90 minutes, the film hits its marks and rolls the credits.

Before I pursue the film’s weightier matters, just a quick word about the connection between the story and Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. It’s the adaptation equivalent of Olive’s sex life: lots of talk, not much fact. It telegraphs its “literary” pretensions without then spending much time on the actual connections. Hester Prynne is Olive’s disguise, and that’s fine because I think the film comes up with some more interesting things to talk about than it would have had it done a Clueless-like spin on Scarlet Letter. That movie already got made. It was called Saved (2004) and it wasn’t nearly as funny or provocative as this one.

The Scarlet Letter stuff (it’s the book Olive is reading in English class) constitutes a scarlet herring because this film really isn’t about being ostracized. In fact, Olive’s adventure actually comes closer than anyone acknowledges to diagnosing modern teen romance. The endless network of cell phones, bathroom gossip, and social media profiles determines who are but can’t provide love. The film’s moral is that you should be careful what you pretend to be because you are what you pretend to be. That seems easy, but if you want love? That’ll take some work.

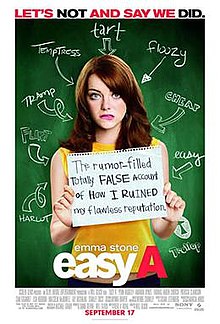

The plot in brief: Olive is an attractive, funny but socially innocuous teenage girl who accidentally starts a rumor about her own sexual exploits. Olive’s initial lie compounds itself when she begins helping out various down-and-out boys earn their sexual stripes (at least in the rumor mill) for monetary considerations.

Olive gets a little lesson in the economics of social capital. Her rapidly disintegrating reputation plunges her into the red. Not even a $200 gift card to Home Depot is going to help her bounce back. She quickly regrets starting the rumor, though her relative social importance skyrockets.

Yet, no one interrogates the warrants that tie a girl’s reputation to her sexual history. We have a fringe Christian group who appears to villainize anyone who acknowledges the existence of MTV. Surely they don’t control the mores of the entire public school! Yet, the school condemns Olive wholeheartedly. There’s no explanation of the double-standard Olive’s being held to, the way that sex constitutes a badge of honor for her male partners but a giant ANATHEMA sticker for her.

Olive responds by tossing off loads of cynical one-liners concerning her situation. How she thought her fake first time would be, you know, special. How the era of chivalry is dead (the era of chivalry being a series of scenes from 80s movies). The longer Olive goes without analyzing the basic social dynamics of her situation—that her romantic fantasies all come from John Hughes movies or that her mom and dad are watching Olive’s final confession on their computers—the more the movie shows love as endlessly alluring and completely fantastical. Emma sees that she’s not the tramp everyone thinks she is, but she remains oblivious to the fact that the entire charade is showing real romantic affection to be a charade too. The big reveal at the end is just an attractive teenage girl talking into a webcam. The milky afterglow is a lawnmower ride down a non-descript California street. Who wants actual intimacy? It’s embarrassing, gives you the clap, and makes you uncomfortable when you have to hear that your parents did it too. The cynicism is funny, but after awhile, it masks desperation. Really? The pinnacle of chivalry is l’enfant terrible Judd Nelson’s defiant upraised fist?

There’s a scene in the final third of the movie that gets played for a laugh but is indicative of this deeper distress. Olive wants—needs to—confess her sins. She seeks out a church, walks into the confessional booth (admitting that her only clue as to how this all works comes from the movies), and proceeds to bear her soul. When she’s greeted with silence, she peeks through the confessional window and sees that no one’s there.

Oh, I get it! God’s dead! Ha ha! The one time she wants someone to listen she gets ignored!

But hey, at least her modern love got her to the church on time. Cue the David Bowie.