Word of the Day: Vainglory

The first word of the day for the new year is vainglory, which www.dictionary.com defines as “excessive elation or pride over one’s own achievements, abilities, etc.; boastful vanity” and “empty pomp or show.” According to www.etymonline.com, the word enters the language way back around “1200, waynglori, from Old French vaine glorie, from Medieval Latin vana gloria.” Vain comes from “Old French vain, vein ‘worthless, void, invalid, feeble; conceited’ (12c.), from Latin vanus ‘empty, void,’ figuratively ‘idle, fruitless,’ from PIE *wano-, suffixed form of root *eue- ‘to leave, abandon, give out.’” Glory comes “from Old French glorie ‘glory (of God); worldly honor, renown; splendor, magnificence, pomp’ (11c., Modern French gloire), from Latin gloria ‘fame, renown, great praise or honor,’ a word of uncertain origin.” Glory can also be a verb, according to etymonline, “’to rejoice’ (now always with in), from Old French gloriier ‘glorify; pride oneself on, boast about,’ and directly from Latin gloriari which in classical use meant ‘to boast, vaunt, brag, pride oneself,’ from gloria.”

According the Christian historian Theodoret (c. 393-c. 460; Bishop of Cyrrhus in Turkey) a monk from Turkey traveled to Rome, following directions from the Holy Spirit, and put an end to gladiatorial combats in Rome on this day in 404 CE.

Here’s a translation: “Book V, Chapter XXVI: Of Honorius the Emperor and Telemachus the monk.

“Honorius, who inherited the empire of Europe, put a stop to the gladitorial combats which had long been held at Rome. The occasion of his doing so arose from the following circumstance. A certain man of the name of Telemachus had embraced the ascetic life. He had set out from the East and for this reason had repaired to Rome. There, when the abominable spectacle was being exhibited, he went himself into the stadium, and stepping down into the arena, endeavoured to stop the men who were wielding their weapons against one another. The spectators of the slaughter were indignant, and inspired by the triad fury of the demon who delights in those bloody deeds, stoned the peacemaker to death.

“When the admirable emperor was informed of this he numbered Telemachus in the number of victorius martyrs, and put an end to that impious spectacle” (http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_telemachus_coliseum.htm).

This might seem like an inconsequential event in the history of the world—a lone monk brings an end to a bizarre form of entertainment through his being stoned to death by the unhappy spectators. So what?

But let me suggest how this little event might be an important step in the transition from the Heroic Age to the Christian Age.

The Heroic Age, which happens at different times in different parts of the world, involved the telling of tales about humans with supernatural strength doing impossible deeds. These tales started out being shared orally and were later written down as a kind of cultural history. Probably the most famous of these oral traditions is that of The Iliad and The Odyssey, supposedly written by Homer, the blind poet. The heroic deeds of the characters in these stories involve violence either against mythical creatures or against other men, and usually against other men.

In the English tradition, the Heroic Age is best exemplified by the epic Beowulf, which, like the Greek epics, probably began its life as an oral tradition (or perhaps traditions) before it was written down. Beowulf, for those of you who have not read it, has the strength of 30 men in his hand, which comes in handy in his battle with Grendel, which, in its first visit to Hrothgar’s hall, ate 30 men. But there are actually at least a couple of poems based on actual historical events, namely “The Battle of Maldon” and “The Battle of Brunanburh,” which also reflect the characteristics of the Heroic Age.

One of the features of the heroes of the Anglo-Saxon literature is that they have to be verbally proficient as well as physically adept. The way the verbal skills manifests is through speeches called flytings. A flyting is “a ritual, poetic exchange of insults practiced mainly between the 5th and 16th centuries. The root is the Old English word flītan meaning ‘quarrel’” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flyting). The characters who engage in these flytings not only insult the other person but also defend themselves against the assertions of their opponents, and the defenses sound an awful lot like boasting. Beowulf tells us how he swam the sea in his armor, with his sword, and fought sea monsters, which is why he lost a swimming race—he killed seven of the monsters who tried to kill him by dragging him to the bottom of the sea. Pretty impressive.

Of course, in order to brag about your physical prowess, you have to have it and use it. You have to fight. In the Heroic Age, and in a heroic culture, fighting is essential to gaining glory. The fact that the glory is essentially transitory, since none of those heroes got to keep the winnings from their heroism beyond their own deaths, makes such boasting seem a bit pointless.

One of the reasons the world is less violent today than at any time in human history (see Pinker, Stephen, The Better Angels of Our Nature, 2011 or Enlightenment Now, 2018) is that we have dropped the reverence for the Heroic ideals. And one of the reasons that we have moved away from the violence of those Heroic ideals is the advent of Christianity, a religion which privileges non-violence and humility, virtues that are not virtues in the Heroic Age.

So Telemachus (the saint, not the son of Odysseus) wins, through his death, an instance of the cultural battle between the ideals of the Heroic Age and those of the Christian Age. Personally, I am glad that the Christian Age won out, for a variety of reasons. But I won’t brag about it, especially since I had nothing to do with it except benefit from it. And bragging would be vainglory.

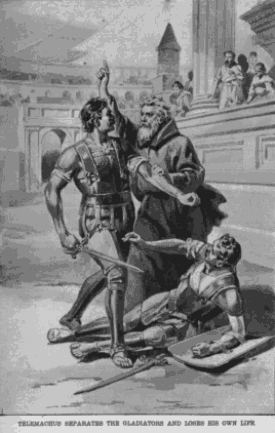

The image is the martyrdom of Telemachus from John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563). Foxe’s version of the story does not agree with Theodoret’s in that Foxe’s version has the gladiators stab Saint Telemachus to death. The caption says, “Telemachus separates the gladiators and loses his own life.”