Word of the Day: Surreal

The word of the day is courtesy of WordThink.com: surreal. Surreal is an adjective that means “Having the disorienting quality of a dream; unreal; fantastic” (http://www.wordthink.com/). According to www.dictionary.com, it also means “of, relating to, or characteristic of surrealism, an artistic and literary style; surrealistic.” It is, in fact, a backformation (something we have discussed recently) from the word surrealism.

Surrealism comes into the language in “1927, from French surréalisme (from sur- ‘beyond’ + réalisme ‘realism’), according to OED coined c. 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire, taken over by Andre Breton as the name of the movement he launched in 1924 with ‘Manifeste de Surréalisme.’ Taken up in English at first in the French form; the Englished version is from 1931” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/surrealism?ref=etymonline_crossreference).

Here’s what www.theartstory.org says about the movement: “The Surrealists sought to channel the unconscious as a means to unlock the power of the imagination. Disdaining rationalism and literary realism, and powerfully influenced by psychoanalysis, the Surrealists believed the rational mind repressed the power of the imagination, weighing it down with taboos. Influenced also by Karl Marx, they hoped that the psyche had the power to reveal the contradictions in the everyday world and spur on revolution. Their emphasis on the power of personal imagination puts them in the tradition of Romanticism, but unlike their forebears, they believed that revelations could be found on the street and in everyday life. The Surrealist impulse to tap the unconscious mind, and their interests in myth and primitivism, went on to shape many later movements, and the style remains influential to this today.”

On December 22, 1737, George Cruikshank wrote the following in his journal: “Died last week, at her lodgings, near the Seven Dials, the much-talked-of Mrs. Mapp, the bone-setter, so miserably poor, that the parish was obliged to bury her” (https://eehe.org.uk/?p=25029). Who was this Mrs. Mapp?

Sarah Mallin was born in 1706 in Epsom, a town in Surrey, England, about 14 miles southwest of London. Her father was a bonesetter, someone who set broken bones, fixed dislocated bones, and manipulated bones somewhat like a chiropractor today (there were no chiropractors in the 18th century). Bonesetters were considered to be less than respectable, at least compared to chirurgeons and apothecaries. But let’s face it: the state of medicine in the first half of the 18th century, even in a relatively wealthy country like England, was not something to write home about.

According to Atlas Obscura, “Known for her temper and brash demeanor (as well as her drinking), Sally often got into fights with her father as she got older. According to a short account of her life in the 1824 book The Cabinet of Curiosities: Or, Wonders of the World Displayed, it was after one such row that she struck out on her own, taking the skills she’d learned and starting her own traveling practice. Leaning into her reputation for bombastic behavior, she operated under the name ‘Cracked Sally—the One and Only Bone-setter.’

“While in Epsom, Sally’s talents became so renowned that she began traveling to London a couple of times a week, where she would take cases at the famed Grecian Coffee House. According to accounts collected in James Caulfield’s 1824 book Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters, of Remarkable Persons: Vol.4., while on these journeys she would travel in a fancy four-horse carriage, carrying with her the crutches of those she had healed, like trophies. It was during one such trip that she was mistaken for King George II’s mistress.

“By 1736, Sally’s rising star was at its apex. The town of Epsom, afraid that she might move on from them, offered her a retainer of 100 guineas a year to continue living and working there. In August of that year, she married her first and only husband, Hill Mapp, despite warnings from friends that he was only marrying her for her increasing wealth. As described in the 1993 book The Alarming History of Medicine, he ‘beat her for a fortnight, then decamped with her money’” (https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/crazy-sally-mapp-bone-setting). But apparently she very quickly decided that 100 guineas was worth getting rid of Mapp.

Unfortunately for Sally Mapp, her drinking and her orneriness caused people to turn away from her. Her clientele diminished, and she ended up dying in poverty.

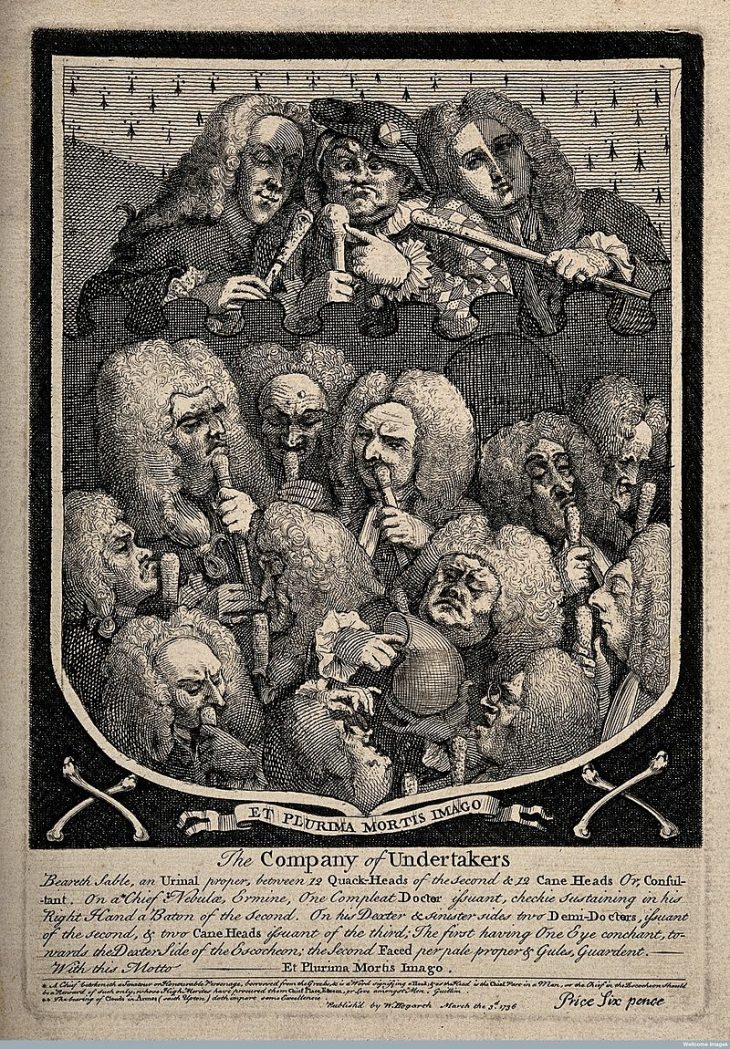

In 1736, at the height of her popularity, William Hogarth included her in a sketch entitled “The Company of Undertakers,” which is described as “A shield containing a group portrait of various doctors and quacks, including Mrs Mapp, Dr. Joshua Ward and John Taylor” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sally_Mapp#/media/File:A_shield_containing_a_group_portrait_of_various_doctors_and_Wellcome_V0010890.jpg), and that is the image she presents is surreal. She is in the center of the top row.