Word of the Day: Charter

Paul Schleifer

According to the OED, a charter is a written document provided “by the sovereign or legislature … granting privileges to, or recognizing rights of, the people, or of certain classes or individuals” or “creating or incorporating a borough, university, company, or other corporation.” Charter can also refer to written evidence of a private contract or a publicly conceded right.

According to www.etymonline.com, the word enters the language around the year 1200, so just in time. It came from “Old French chartre (12c.) ‘charter, letter, document, covenant,’ from Latin chartula/cartula, literally ‘little paper,’ diminutive of charta/carta ‘paper, document.’”

This will be two days in a row of talking about English kings. Please don’t worry that it will become a habit.

On this date in 1199 CE, King Richard I, known as King Richard Cœur de Lion or Richard the Lionheart, was wounded by a bolt from a crossbow. Because of the unfortunate lack of antibiotics in medieval Europe, the wound became infected and gangrenous, and Richard died 12 days later. One might expect that he died gloriously in battle, but that’s not actually what happened.

It is true that Richard earned his epithet because of his success as a military leader, and in the Middle Ages that meant not only as a strategist but also as a fighter himself. At 16 he already led his own army against rebels against his father, Henry II. He was at first second to Philip II of France in the leadership of the Third Crusade, but when Philip left, he became the leader and defeated Saladin several times in battle, though he never regained the city of Jerusalem.

Like his father, Richard was not only the King of England but also the “Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and … overlord of Brittany” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_I_of_England). The focus of Richard and Henry and those before them, going back to William, was the territories in France; for instance, Richard spoke French and Occitan, a language spoken in southern France and northern Italy. He did not speak English, a language that was in transition at that time from Old English to Middle English.

Just a year after his coronation, Richard set off for the Holy Lands. He left his lands in charge of three regents, to the disappointment of his younger brother John. On his return two years later, Richard was first taken prisoner in Duke Leopold of Austria and then by Henry VI, the Holy Roman Emperor. In his absence, his younger brother John rebelled against the regents, formed an alliance with Philip II, and even told people that his brother was dead.

Finally, Richard returned in 1194 and took his kingdom back. John had left England and retreated to Normandy, where Richard finally caught up with him. Richard not only forgave John, but he also declared that John was his heir apparent. When Richard died in 1199, John became the King of England.

Many consider Richard to have been one of the great kings of England. Not me. Richard liked going to war; he practically bankrupted his kingdom going to war; he got a lot of other people killed going to war. John, on the other hand, is considered one of the least good kings in English history. His epithet was not “Lion Hearted” but “Lackland,” in reference to all the French lands that he lost to Philip II. Of course, it’s not that he didn’t try. He tried to take back Normandy from Philip in 1214, but after a good start, his campaign fizzled, and he returned to England to face rebellion from the barons.

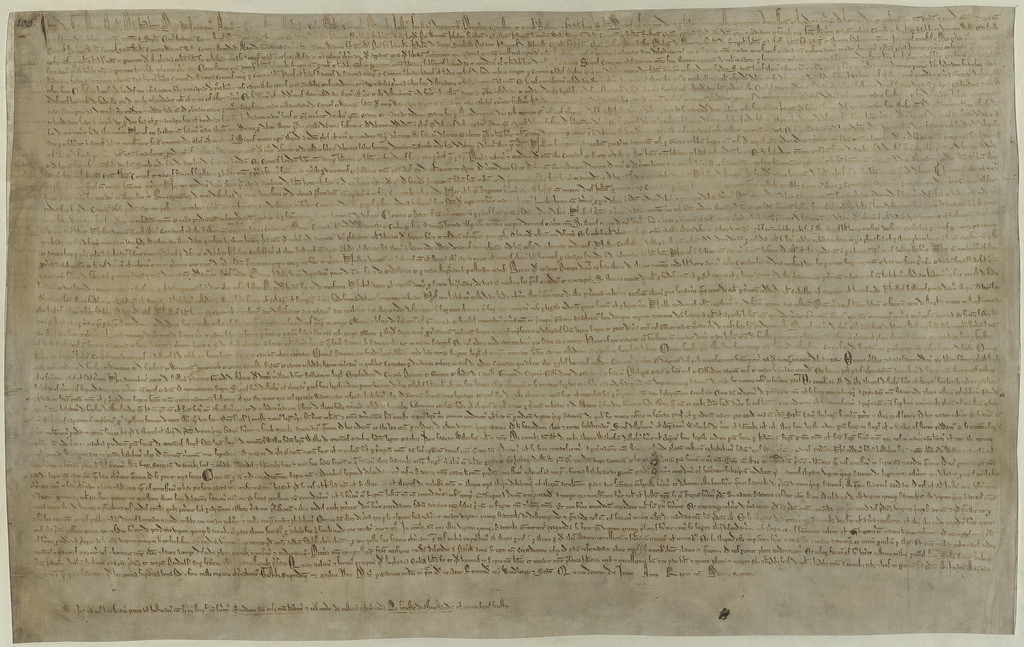

Most importantly, perhaps, John signed the Magna Carta, the Great Charter of the Liberties. He didn’t want to. The rebel barons (which was most of the barons) had renounced their oaths of fealty to him, and they were militarily stronger, and he was not much of a military leader. So he was not in a good spot.

The Magna Carta is the beginning of England’s long history of participatory government. It guaranteed the barons especially but also others, including servants, certain rights, including the right to be free from illegal imprisonment.

John quickly walked back his promise to abide by the Great Charter, leading to a renewal of hostilities. The resulting fighting led to John’s death, not in battle, of course. While campaigning in 1216, John came down with dysentery, and he died. His son, Henry III, renewed the Great Charter, and it was renewed again in 1297. So unwittingly, John Lackland began the tradition of limited government and civil rights that would eventually lead to a constitutional monarchy and Parliament in England, and the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution here in the U.S.

And it all began with a little piece of paper, a charter.

The image is of “The Magna Carta (originally known as the Charter of Liberties) of 1215, written in iron gall ink on parchment in medieval Latin, using standard abbreviations of the period, authenticated with the Great Seal of King John. The original wax seal was lost over the centuries. This document is held at the British Library and is identified as ‘British Library Cotton MS Augustus II.106.’” Robert Cotton was a collector of old manuscripts, and he had them on bookshelves in front of which were the busts of Roman Emperors. Among other manuscripts found in the Cotton library were the Beowulf manuscript (Cotton Vitellius A 15) and the Gawain manuscript (Cotton Nero A 10). The Cotton library originally contained two of the four surviving copies of the 1215 Magna Carta.