Word of the Day: Marathon

Today’s word of the day, thanks to the Dictionary Project, is marathon. Marathon is a noun that means “a foot race that covers a distance of 26 miles, 385 yards (42 .195 km), “any long distance race,” “any contest or event of a great duration that requires endurance,” or “a lengthy activity or task that requires prolonged stamina, attention or effort” (The Dictionary Project daily email, April 5, 2024). Notice that it is a word that has undergone linguistic broadening or generalization, moving from a very specific meaning in athletics to a broader meaning in athletics to a general meaning of anything that takes a long time and a lot of effort: “I turned my dissertation into a real marathon.”

Here is what the etymology website has to say: “1896, in marathon race, ‘long-distance foot-race of 26 miles, 385 yards,’ named for the town of Marathōn, in Attica, site of a famous battle in antiquity. The place-name is literally ‘fennel-field, fennel’ (Greek marathon), probably so called because the herb grew nearby. It is a word of uncertain etymology; Beekes writes, ‘For a plant name, foreign origin is suspected.’

“The race was introduced as an athletic event in the 1896 revival of the Olympic Games. It is based on the story of the Greek hero Pheidippides, who in 490 B.C.E. ran to Athens from the Plains of Marathon to tell of the allied Greek victory there over Persian army.

“The oldest form of the story (Herodotus) tells that he ran from Athens to Sparta to seek aid, which arrived too late to participate in the battle (but approved the tactics). The 1896 Olympics chose a later story, less likely but more dramatic, that Pheidippides ran to Athens from the battlefield with the good news.

“The 1896 course began in the town of Marathon and finished in Athens’ Panathenaic Stadium; the precise distance of the race fluctuated until after 1924.

“From the distance-race, the word was extended generally to mean ‘any very long event or activity’” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=marathon).

It is not unusual for the name of something—a place, a product, even a person—to be derived from the name of a person or a place. These are called eponyms. For instance, Britain is, supposedly, derived from the country’s mythical founder Brutus.

So here is the story of the marathon as told by Dean Karnazes on the Runner’s World website: “Pheidippides was not a citizen athlete, but a hemerodromos: one of the men in the Greek military known as day-long runners” (https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a20836761/the-real-pheidippides-story/). “Comparatively little is recorded of the mysterious hemerodromoi other than that they covered incredible distances on foot, over rocky and mountainous terrain, forgoing sleep if need be in carrying out their duties as messengers” (ibid.).

Karnazes says that Pheidippides, before he ran from Marathon to Athens to announce the Athenian victory over the Persians, ran from Athens to Sparta, a distance of about 150 miles, to enlist the aid of the Spartans. He convinced them to join the Athenians, but they delayed because they were in the middle of a religious holiday. So the next morning, Pheidippides made the return trip, another 150 miles. Based on Pheidippides’ news, the Athenian general attacked. He knew that the Persian cavalry had returned to their ships in order to sail down the coast and attack Athens itself. So on the field of Marathon, the Greeks won a battle of the ages.

But what about Athens? A runner, perhaps Pheidippides, made the run from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory and warn the city about the Persians planning to attack the city. As a result, the city was prepared enough to prevent the Persians from landing.

According to the wiki: “The battle was a defining moment for the young Athenian democracy, showing what might be achieved through unity and self-belief; indeed, the battle effectively marks the start of a ‘golden age’ for Athens. This was also applicable to Greece as a whole; ‘their victory endowed the Greeks with a faith in their destiny that was to endure for three centuries, during which Western culture was born’. John Stuart Mill’s famous opinion was that ‘the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings’. According to Isaac Asimov, ‘if the Athenians had lost in Marathon, . . . Greece might have never gone to develop the peak of its civilization, a peak whose fruits we moderns have inherited.’

“It seems that the Athenian playwright Aeschylus considered his participation at Marathon to be his greatest achievement in life (rather than his plays) since on his gravestone there was the following epigram:

This tomb the dust of Aeschylus doth hide,

Euphorion’s son and fruitful Gela’s pride.

How tried his valor, Marathon may tell,

And long-haired Medes, who knew it all too well.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Marathon).

And what about Pheidippides? After his glorious run from Marathon, and after proclaiming the victory and warning of the coming Persian invasion, he dropped dead. And I tell this story to people who tell me that they are in training to run a marathon. I think they need to know.

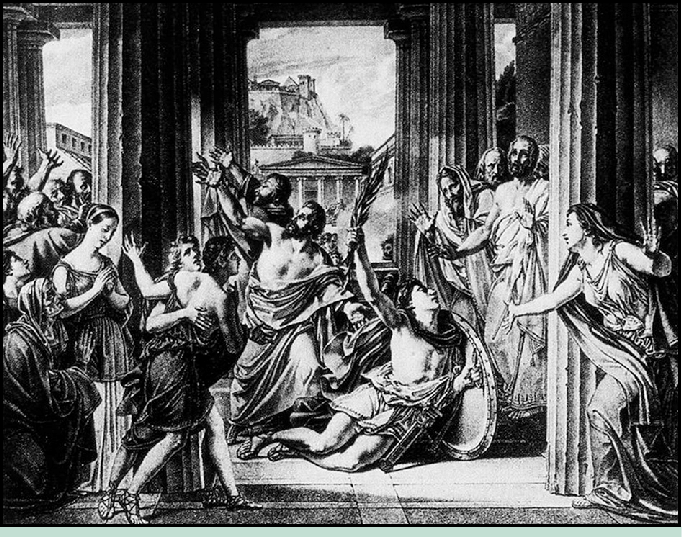

The image today is a painting of “Pheidippides’ sudden cardiac death in the Atheneum in 490 BC after declaring victory over the invading Persian army on the plains of Marathon (by anonymous)” (https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Pheidippides-sudden-cardiac-death-in-the-Atheneum-in-490-BC-after-declaring-victory-over_fig1_275365929). Interestingly, the website connects to an article entitled “Fatal Water Intoxication and Cardiac Arrest in Runners During Marathons: Prevention and Treatment Based on Validated Clinical Paradigms” in The American Journal of Medicine 128(10), April 2015.