Word of the Day: Job

Today’s word of the day is job, but not in its usual sense. I came across this today on the www.thoughtcatalog.com website in a list called “500 Archaic Words That Everyone Really Needs To Use Again” by Jerome London (September 17, 2018). In the archaic sense it is a verb meaning to “turn a public office or a position of trust to private advantage.” According to www.dictionary.com, it can also be a noun meaning “a public or official act or decision carried through for the sake of improper private gain.” The website www.etymonline.com says that the meaning “pervert public service to private advantage” comes from 1732.

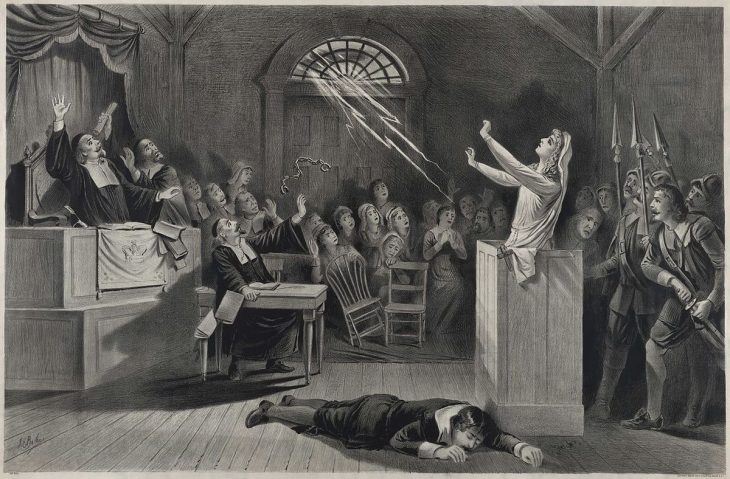

On this date in 1692, Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba were arrested and interrogated because of accusations of witchcraft in the town of Salem (now Danvers), Massachusetts. Their accusers were 9-year-old Betty Parris, 11-year-old Abigail Williams, 12-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr., and 17-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard. Sarah Good was poor; Sarah Osborne didn’t regularly attend church services; and Tituba was a slave imported from the West Indies. Each was ripe for such accusation because they were different from the average Puritan woman.

Later in March, Martha Corey, Dorothy Good (the 4-year-old daughter of Sarah Good), and Rebecca Nurse in Salem Village were all arrested. Corey was arrested because she questioned the believability of the accusations. Little Dorothy was interrogated by the court, and some of her answers led the court to believe that she and her mother were both involved in witchcraft. And while the first three arrested were all outsiders, Corey and Nurse were upstanding, covenanted members of the church.

The trials continued for through 1692 and until May of 1693. In toto, more than 200 people were arrested, 30 convicted, 19 executed, and one (Giles Corey) pressed to death for refusing to enter a plea. The last is one of the most interesting stories from the tragedy: Corey refused to plead either not guilty or guilty. According to the law of the time, a person could not be tried without a plea. The way they tried to force the accused to plead was to press him or her: they would strip the accused, place heavy boards on him or her, and then begin piling rocks on the victim. Corey, when asked what he would say, was reported to have replied either “more weight” or “more rocks.” It took two days, but he was finally pressed to death.

If you have ever seen Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, you may think that the real cause of the madness was the illicit affair between John Proctor and the teenage Abigail Williams, but the real Williams was only eleven. Scholars now think that the real cause of the accusations was more mundane. Salem was known for the contentiousness of its population. Before the congregation hired Samuel Parris to be their minster, the two previous ministers had left the pulpit in Salem because, they said, the church had refused to pay them what they were owed. The people fought over property lines, grazing rights, and the church.

But another aspect of the Salem Witch trials may have been mass hysteria. In fact, the episode is sometimes called the largest example of mass hysteria in Colonial American history. As the accusations of witchcraft were thrown around, people began to fear witchcraft so much that they began to see it almost literally everywhere. Such hysteria can affect people.

We are witnessing another kind of hysteria today. Even though the new coronavirus was affected a minute portion of the population, many people are terrified by it. The experts have suggested that it may be 10 times more deadly than the seasonal flu, but that means that people who get it have a 1% chance of dying (though I have seen .67% as well, and both of those numbers are suspect because we do not know how many of the people in China, where the “pandemic” started, have had the virus without reporting to a hospital).

One of the results of the hysteria regarding the coronavirus is that I am seeing advertisements for masks to filter the virus out of the air. And it is true that people are starting to wear such masks when out in public.

But while the corona virus may be 10 times more deadly than the seasonal flu virus, one is far more likely to get the seasonal flu virus than the coronavirus. So far more than 75,000 people have been identified as suffering from the coronavirus, with 2,000 of them having died (most of the victims have been in mainland China). In comparison, the seasonal flu has caused 26 million cases, with 250,000 going into the hospital, and 14,000 dying. And that is just in the USA. Worldwide numbers are far, far greater. In other words, every year a person has a far greater chance of dying by the flu virus than they have of dying from this year’s new corona virus.

Of course, the seasonal flu is far from being the deadliest disease in the world. In the USA, while over 50,000 people die from the flu each year, well over 600,000 people die from heart disease, and almost 170 thousand die from accidents. If a person is so worried about the coronavirus that they will spend money buying a mask to wear in public, they should be spending a lot more money to lose weight and get in shape, and they should probably do a lot more to protect themselves from accidents. In 2017, 675 children (12 and younger) died in car accidents, and 35% of them were not buckled up.

But the hysteria continues. The hysteria is propagated by the news media, who spend an inordinate amount of time talking about this terrible killed. It is also spread by politicians who want to use it to paint a picture of the callousness or incompetence of their opponents. And apparently it is being used by the manufacturers of different kinds of masks, even though the experts are telling us that you don’t need to wear a mask unless you are the one who is sick.

But there are people who will use the coronavirus just as there were people who used accusations of witchcraft to get something that they want—power, material goods, revenge, or who knows what? That these people are giving the rest of us the job should be disturbing.

The picture is a drawing of the witch trials by Joseph E. Baker, “The Witch No. 1,” 1892.