Word of the Day: Gype

Today’s word of the day, thanks to the Oxford English Dictionary, is gype, a noun which has changed meaning during the centuries. The earlier definition was “A glutton; a greedy or avaricious person,” a definition labeled “obsolete” by the OED. The later definition is “A fool, an idiot.” The OED says that the noun is northern, coming from Scotland or Ireland. Also, since it is the OED, it gives quotes for both definitions, and the most recent quote for the second definition is from just three years ago: “2017 Aberdeen Evening Press (Nexis) 31 Mar. 16 Daft gypes these days pay a fortune for ragamuffin troosers that make them look like they’ve just crawled out of a gorse bush.” The American pronunciation of the word is /ɡaɪp/, with a hard g sound rather than the soft g of genius.

I found gype on www.yourdictionary.com, giving it the newer definition, “(Ulster) fool; clumsy, awkward person; long-legged person; silly girl,” adding, “Origin From Scots gype (‘foolish, awkward person’) (compare Old Norse geip (“nonsense”)).” The Merriam-Webster Dictionary website also uses the definition “fool,” but it adds the definition of an intransitive verb, “to stare like a fool” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gype). Interestingly, both the dictionary.com and the etymonline.com websites have nothing for gype. Merriam-Webster also gives this as an etymology: “of Scandinavian origin; akin to Old Norse geip nonsense, geipa to talk nonsense, gīpr mouth, throat, Norwegian dialect geipa to talk nonsense; akin to Middle Dutch gīpen to gasp, Old English gīpian, geonian to yawn.” The OED also gives a derivative, gypery, meaning “foolish or silly behavior; nonsense.”

Yesterday, a friend who is also a pastor asked me about literary depictions of the seven deadly sins. We don’t think much about the seven deadly sins anymore. One might say that we don’t even think about sin much anymore, at least not in the public sphere, but when we do, it is more likely to be sins against political correctness than against any sort of Biblical norm. One certainly won’t find much about the seven deadlies in contemporary literature. So I had to go back in time, to the Middle Ages, to think of something that would help him out.

What are the seven deadly sins? Without the capital letters, they are not a Japanese manga series in which a princess is looking for a group of seven Holy Knights who were disbanded after the fall of the kingdom. No. The seven deadly sins are the really serious sins, according to the Roman Catholic Church. They are pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath (or anger) and sloth (or laziness or indolence). They are contrasted by the seven heavenly virtues, which are the four classical virtues, prudence, justice, temperance, and courage (or fortitude) combined with the three specifically Christian virtues of faith, hope, and charity (see 1 Corinthians 13: 13, “And now abideth faith, hope, and charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity” [KJV]). Charity is, by the way, an old word for love.

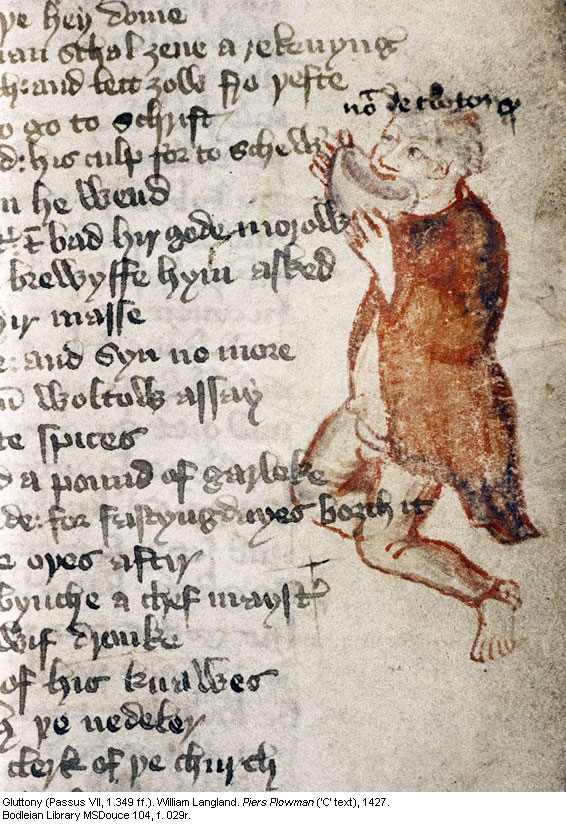

The literary work I pointed my friend to is Piers Plowman (or, William’s Vision of Piers Plowman, or The Vision of Piers Plowman, or The Vision and Creed of Piers Plowman [or Ploughman]). Written between about 1367 and the 1380s, maybe as late as 1390, Piers Plowman is a dream-vision poem (like Dante’s Comedia) and an allegorical poem (like Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress). In it, the character Will, who is the first-person narrator, has a series of dream visions. In these visions, he goes on an allegorical quest looking for the good Christian life. He meets numerous characters, including Piers the Ploughman, who is the model of the good Christian life.

The poem is divided in passus (steps), and it is Passus V that Will encounters the Seven Deadly Sins, who are confessing; well, most of them are confessing. Gluttony doesn’t quite make it.

Gluttony is on his way to the church to be shriven (to confess his sins and receive absolution) when he passes the tavern. Betty the brewer sees him out the door and calls to him: “I’ve good ale, good friend,” she says, and the invitation is too much for Gluttony to withstand. He goes into the tavern just to try the ale, just to have one, before he heads on to church. But inside the tavern are some of Gluttony’s friends: Cissy the seamstress, Wat the warren-keeper and his wife, Tim the tinker, Dave the ditch-digger, and more than a dozen others. They all greet Gluttony (I always think of Norm entering Cheers when I read this passage), and they drink and play games.

Before long, Gluttony is quite drunk. He begins to leave, but he doesn’t get far:

But as he started stepping to the door his sight grew dim;

350 He felt for the threshold and fell on the ground.

Clement the cobbler caught him by the waist

To lift him aloft, and laid him on his knees.

But Glutton was a large lout and a load to lift.

And he coughed up a custard in Clement’s lap.

355 There’s no hound so hungry in Hertfordshire

That would dare lap up that leaving, so unlovely the taste.

Gluttony gets home and sleeps for two days; when he finally awakes, he gets an earful from his wife, and he finally confesses.

Part of the point of this passage, besides its humor, is to show how gluttony leads to other sins: drunkenness, swearing, sloth, and others. The funny thing is that the truth of the passage has not changed in the 600+ years since the poem was written. And yet gluttony is not a sin that we talk about very much in 21st century America. We are quite concerned with sexual sin, but we give gluttony a pass. I read, a few years ago, about a pastor near where I live who had to retire because he could no longer climb up into the pulpit. I would like to think that there was a hormonal problem, but the truth is that a person doesn’t hit 400 pounds without having a serious excess of calories on a daily basis.

When I look at the definition of gype, I see, in my mind’s eye, someone who is greedy and grasping. But gluttony can look normal, even innocent. No matter how it looks, gypery is a sin.

The image is from the Bodleian MS Douce 104 (a manuscript named for Francis Douce who donated it to the Bodleian Library in 1834); it portrays Gluttony from Passus V, in the C-Text, the third version of Piers Plowman.