Word of the Day: Pithy

Today’s word of the day, thanks to the GRE Word of the Day website, is pithy. I mean, of course, that the word we are going to define is the word pithy, not that the word of the day is pithy. I try to be pithy, but given that I am an English professor, it is very hard for me. So what does pithy mean? According to www.dictionary.com, the word is an adjective meaning “brief, forceful, and meaningful in expression; full of vigor, substance, or meaning; terse; forcible” or “of, like, or abounding in pith.” Pith comes from biology and refers to the center of the stalk of certain kinds of plants, and then, metaphorically, to the center or heart of something in general, even something abstract. And according to www.etymonline.com, pithy first appears in English in the early 14th century, a long time ago.

On this date in 1921, almost 100 years ago, a play premiered at the National Theater of Prague in Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). The play had been published the year before by the Aventinum Publishing House. It was translated into English by Paul Selver and premiered in the United States in 1922 and in England in 1923. The New York production, at the Garrick Theater, featured the Broadway debuts of two American actors who would become quite famous: Spencer Tracy and Pat O’Brien. The play also introduced a word into English that has had a lasting impact.

The play was entitled Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, or Rossum’s Universal Robots in English, written by Karel Čapek. According to Encyclopedia Brittanica, “The son of a country doctor, Čapek suffered all his life from a spinal disease, and writing seemed a compensation. He studied philosophy in Prague, Berlin, and Paris and in 1917 settled in Prague as a writer and journalist. From 1907 until well into the 1920s, much of his work was written with his brother Josef, a painter, who illustrated several of Karel’s books.” Čapek wrote in a wide variety of genres and on a variety of topics. His most productive years were during the period of the First Czech Republic, 1918 to 1938. He was especially concerned with tyranny and fascism. He died on Christmas Day of 1938, before he could see his beloved country invaded by the National Socialists of Germany.

In the play, Rossum and his son have invented mechanical workers, called robots, after the Czech word robota, or forced labor. The idea is that these complex machines can replace human beings in doing the kind of labor that human beings find drudgery. A young woman visits the island where these creations are manufactured to try to win rights for them. But ultimately, the robots decide that the real threat is from human beings, and they decide to rid the planet of all people. But by the end, the two principal robots, Primus and Helena, are well on their way to becoming human themselves.

The play was well received wherever it played, though apparently the original translator did some editing that was not approved by the author. A 1995 translation is truer to the original story than the one from the early 1920s.

The robots that Čapek and his brother, Josef, conceived were not the metal creations that we often imagine when we think of robots, like Robby the Robot in the original Lost in Space series or the robots in the I, Robot movie. Their robots (and I should say here that Karel Čapek gave the credit for the coining of the word to his brother) were more like the replicants of the movie Blade Runner, artificial but biological creatures.

While the play was received well by a lot of critics, one famous science fiction writer who was quite involved in the popularization of robots, was pretty critical. Isaac Asimov considered “R.U.R. as ‘a terribly bad’ play, but ‘immortal for that one word’ and as his inspiration to write the Three Laws” of robotics that informed his robot stories and robot novels, including the second Foundation trilogy.

The idea of scary, super-intelligent artificial creatures has been around for a pretty long time. Perhaps the most popular version of this creature before the 20th century was Mary Shelley’s creature in the novella Frankenstein. But Karel and Josef Čapek gave us a powerful picture of this scary creation, a predecessor to the replicants of Blade Runner and the cyborgs of the Terminator movies.

But that was probably not what the Čapek brothers were really trying to create when they wrote R. U. R. They were more likely making a statement about the dehumanizing effect of tyrannical control over people. Keep in mind that robot is associated with the kind of required, unpaid labor that serfs were required to perform for the benefit of their “lord.” If you ever get the chance to see a production of R. U. R., perhaps you can write and let me know if it is really about scary robots or a pithy reflection of the dehumanizing effect of tyranny.

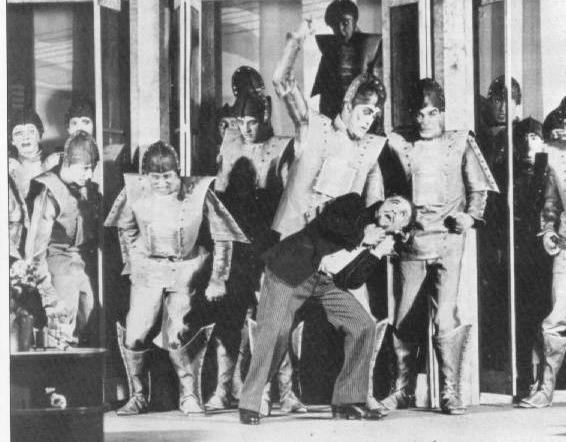

The photograph is from the “Theatre Guild touring company’s 1928–1929 production of R.U.R. by Karel Čapek.” It’s from Act 3, when the robots break into the factory where they were produced and kill all the humans except for one.