Word of the Day: Svengali

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Word Genius, is Svengali. It’s a noun meaning “A manipulative person with sinister motives” or “Someone attempting to dominate another to do their bidding” (https://www.wordgenius.com/all-words/svengali?utm_source=R1D&utm_medium=R1D&utm_campaign=1065678355&utm_content=7140730&utm_term=1006016780). Dictionary.com defines it as “a person who completely dominates another, usually with selfish or sinister motives.” The website adds, “First recorded in 1940–45; after the evil hypnotist of the same name in the novel Trilby (1894) by George Du Maurier.” If you were wondering why the word is capitalized, it is because it is a proper noun used as a common noun.

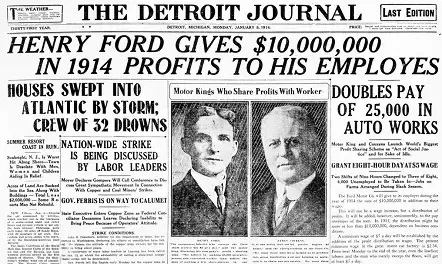

On this date in 1914, Henry Ford somewhat famously “doubled” the wages of his employees. Or at least that is what people say.

“Higher wages were necessary, Ford realized, to retain workers who could handle the pressure and the monotony of his assembly line. In January of 1914, his continuous-motion system reduced the time to build a car from 12 and a half hours to 93 minutes. But the pace and repetitiveness of the jobs was so demanding, many workers found themselves unable to withstand it for eight hours a day, no matter how much they were paid.

“But Ford had an even bigger reason for raising his wages, which he noted in a 1926 book, Today and Tomorrow. It’s as a challenging a statement today as it as 100 years ago. ‘The owner, the employees, and the buying public are all one and the same, and unless an industry can so manage itself as to keep wages high and prices low it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers. One’s own employees ought to be one’s own best customers’” (https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2014/01/ford-doubles-minimum-wage/). Of course, the article in the Saturday Evening Post was sponsored by the Ford Motor Company—no conflict of interest there.

The article continues, “While it worked, though, Ford’s $5.00-a-day policy helped the company achieve record profits. It made its cars affordable to its workers (who could purchase a Model T with four months’ wages.) It helped put 15 million Americans behind the wheel of an automobile. And it set a standard for wages that, despite all the predictions of doom for the Ford Motor Company, every other car company eventually adopted.”

It sounds like a truly noble action on the part of Henry Ford, and he wanted people to believe that.

But that depiction is simplistic and self-serving. A more detailed analysis by Forbes includes the following facts:

Turnover at the Ford Motor Company was very high. In 1913, Ford hired, during the course of the year, 52,000 people to maintain a workforce of 14,000 (https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2012/03/04/the-story-of-henry-fords-5-a-day-wages-its-not-what-you-think/#3834c46c766d). A high rate of turnover is very expensive for a company—new employees need to be trained, and workers who leave often leave quite suddenly, without giving their 2 weeks’ notice–so paying a higher wage for what was apparently stressful (or incredibly boring) work was an inducement to the workers to stay. In this way, Ford was actually able to save the company money.

The $5/day wage didn’t have to be a “living wage,” whatever that might mean; it only had to be better than other employers were paying in order to make the workers feel as if they were getting a really good deal. This is the problem with the push for a $15/hour minimum wage, as even leftist economist Paul Krugman admits: “But in any case there is a fundamental flaw in the argument: Surely the benefits of low turnover and high morale in your work force come not from paying a high wage, but from paying a high wage ‘compared with other companies’–and that is precisely what mandating an increase in the minimum wage for all companies cannot accomplish” (https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2012/03/04/the-story-of-henry-fords-5-a-day-wages-its-not-what-you-think/#3834c46c766d).

Apparently, it was also not a simple $5/day wage. The $5 was made up of a wage and a bonus, and the bonus was based upon social behavior: “The $5-a-day rate was about half pay and half bonus. The bonus came with character requirements and was enforced by the Socialization Organization. This was a committee that would visit the employees’ homes to ensure that they were doing things the “American way.” They were supposed to avoid social ills such as gambling and drinking. They were to learn English, and many (primarily the recent immigrants) had to attend classes to become “Americanized.” Women were not eligible for the bonus unless they were single and supporting the family. Also, men were not eligible if their wives worked outside the home.” Such behavioral monitoring would be quite unacceptable today, but in the 1910s and 1920s, the fear of, particularly, drinking alcohol was such that many workers probably accepted the monitoring.

In essence, the $5/day wage and bonus was more than just an attempt to create customers for the Model T. It was an attempt to create model employees who would be sober, who would show up every day, and who would feel loyal to Henry Ford. So the $5/day wage was really a kind of Svengali move designed to provide Ford with the ideal workforce. Of course, nowadays we have the entire education establishment to do the same thing.

I think today’s image is kind of obvious, isn’t it?