Word of the Day: Certitude

Paul Schleifer

www.etymonline.com says that certitude comes into the language in the “early 15c., from Middle French certitude ‘certainty’ (16c.), from Late Latin certitudinem (nominative certitudo) ‘that which is certain,’ from Latin certus ‘sure, certain,’ originally a variant past participle of cernere ‘to distinguish, decide,’ literally ‘to sift, separate.’ This Latin verb comes from the PIE root *krei- ‘to sieve,’ thus ‘discriminate, distinguish,’ which is also the source of Greek krisis ‘turning point, judgment, result of a trial.’”

According to the OED, certitude means “absolute certainty or conviction that something is the case.”

On this date in 1772, Emanuel Swedenborg died at the age of 84. Born in Stockholm in 1688, Swedenborg lived, essentially, two lives.

He was born Emanuel Swedberg and raised in Stockholm. At Uppsala University Swedenborg studied physics and mechanics, as well as dabbling in philosophy and poetry. For a couple of years, he published a scientific journal. Sweden’s King Charles gave him a position on the Board of Mines, an important post at the time because mining was a large part of Sweden’s economy. Charles died in 1718 and was succeeded by his sister, Ulrika Eleonora, who ennobled the Swedberg family; from that point on, the family was known as Swedenborg.

Then, in his 40s, even while continuing his position as assessor of mines, he took up the study of anatomy and physiology, making some prescient suggestions about neurons, nerves, and the cerebral cortex, among other things. Some of his ideas have since been verified by modern scientific techniques. He also published a work on mechanics and philosophy, Opera philosophica et mineralis (“Philosophical and mineralogical works“). And it was in this era that he began to develop an interest in the connections between science and the spiritual world.

Beginning in 1743, Swedenborg, who was raised as a Lutheran, began to undergo a spiritual crisis. In 1744, he asked for a leave of absence from his position with the Board of Mines in order to write, but his original project, The Animal Kingdom, which had been planned for 17 volumes, was interrupted by dreams and visions; these dreams drew Swedenborg more and more to a consideration of the spiritual. Beginning in 1745, he began to keep a journalistic record of his visions. In addition, he began to write about his faith experiences.

Thus began Swedenborg’s second life.

In 1749, Swedenborg published his first overtly religious work, Arcana Coelestia (Secrets of Heaven). It was a verse by verse exegesis of Scripture, and he had planned to continue doing it. He never did, but he did write numerous other works on his understanding of the Christian faith.

I’ll let the Swedenborg Foundation tell the next part of the story:

“Starting in 1759, however, a series of incidents demonstrating Swedenborg’s interactions with the spirit world drew international attention. The first, in July 1759, happened while Swedenborg was attending a dinner party in the Swedish city of Göteborg. During the party, he suddenly became agitated and began describing a fire in Stockholm—more than 250 miles away—that was threatening his home. Two hours later, he reported that the fire had been extinguished three doors down from his house. It was not until two days later that messengers from Stockholm arrived in Göteborg and confirmed the details as Swedenborg had relayed them.

“In 1760, the widow of the recently deceased French ambassador to Sweden was presented with a bill for a very expensive silver service her husband had bought. She was sure he had paid, but could not find the receipt. After asking Swedenborg for help, she had a dream in which her husband revealed the location of the receipt, a dream which turned out to be accurate.

“In 1761, Swedenborg was presented at the court of Sweden’s Queen Louisa Ulrika (1720–1782), and she asked him to relay a particular question to her deceased brother, Prince Augustus Wilhelm of Prussia (1722–1758). Swedenborg returned to court three weeks later and gave her the answer privately, upon which she was heard to exclaim that only her brother would have known what Swedenborg had just told her.

“These three well-documented incidents, in conjunction with some others, made Swedenborg the subject of conversation not just in his own country, but in continental Europe as well” (https://swedenborg.com/emanuel-swedenborg/about-life/).

He developed quite a following around the world, and he continued to write. And as the website indicates, Swedenborg continues to have a following today.

It is hard for me to believe that Swedenborg’s visions were anything legitimate, but he certainly had certitude in them.

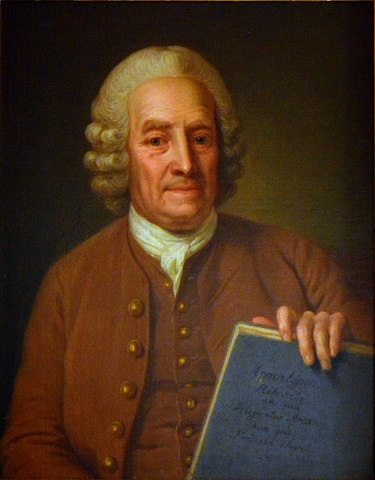

The image is a portrait of Swedenborg at the age of 75, holding Apocalypsis Revalata. It was painted by Per Krafft the Elder in 1766.