Word of the Day: Sanguine

Paul Schleifer

If you look in a regular dictionary, the first definition of sanguine that you are likely to find will be something like “cheerfully optimistic, hopeful, or confidence.” But if you look in the Oxford English Dictionary (a dictionary built upon historical and etymological principles), you won’t find that definition until you get down to definition #4. The first definition of sanguine in the OED is “Blood-red,” first documented in the Wyclif Bible, the Book of Ecclesiasticus 45:12: God gave to him an holy stole, with gold, and blue violet silk, and sanguine silk, the work woven, through the doom of the wise man, and through the truth of the adorned…” (https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Ecclesiasticus+45%3A10-12&version=WYC). The second OED definition is “Of or pertaining to blood; consisting of or containing blood,” though it says that this meaning is “rare” (and I am wondering if the editors of the OED are engaging in double entendre there). A “b” definition under number 2 is “Causing or delighting in bloodshed; bloody,” which seems gruesome today, particularly in light of the word’s meaning in modern parlance.

The third definition of sanguine in the OED is longer: “In mediæval and later physiology: Belonging to that one of the four ‘complexions’ (see complexion n. 1) which was supposed to be characterized by the predominance of the blood over the other three humours, and indicated by a ruddy countenance and a courageous, hopeful, and amorous disposition” (http://www.oed.com.libproxy.clemson.edu/view/Entry/170657?rskey=ODpPOQ&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid). So here we are getting into the medieval theory of the humors (a theory that actually predates Hippocrates), which was that the human body contains four fluids: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. It’s more complicated than I want to get into, but suffice it to say that when a person has too much blood, compared to the other three, they will have a sanguine personality.

And thus we get to the fourth definition, the one which people usually are aware of.

On this date 130 years ago, the first meeting of the Football League took place.

Some background: football has been around for a very, very long time. It probably goes back at least to the Roman Empire. In England, it is likewise hard to say when and where it started. And for centuries the rules of the game were different depending upon where you played. Boys played the game at school, but each school, or schools in each area, had its own set of rules, and when the boys went on to university, they found chaos. In 1848, Cambridge University adopted a set of rules which many followed. But in the 1850s, the Sheffield Rules were created and used by clubs in northern England. Finally, eleven clubs got together to create a list of common rules in 1863, and the Football Association (FA) was born. Even with this association, clubs were responsible for creating their own schedules, which caused great inconsistency, particularly in revenue for the different clubs.

It took a decade for the London Association and the Sheffield Association to finally give in to the advantages of having a single set of rules, but they did. In 1871, the FA began the longest-running association football (what we in the States call soccer, from the word association) competition in the world, the FA Cup. At the time, the clubs consisted of amateur players, and paying players to play was against FA rules. Nevertheless, many clubs, in their desire to win, began to cheat (oddly, none of these clubs was called the Patriots!).

Then, in 1888, William McGregor, a director of the Aston-Villa club, organized a meeting of representatives from Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, Stoke (later Stoke City), and West Bromwich Albion with the intent of creating a league that would guarantee a regular schedule for all the members of the league. In September of that year, league play began with 12 member clubs.

In 1892, a second division was formed, and the Football League absorbed the Football Alliance. Some of the clubs in the Alliance were added to the First Division, and a system of relegation was eventually created.

About 100 years after the second division was formed, 22 teams broke away from the Football League to form the English Premier League, the richest football league in the world, though it was very quickly re-absorbed into the FA.

One of the things I really like about English football, unlike the American MLS and the USL leagues underneath it, is relegation. If you’re a fan of a small city club that plays in a USL league, like Bethlehem Steel FC, you know that your club will never be in the MLS. But if you’re a fan of Lincoln City FC, which currently resides in 8th place in League Two (the fourth highest league in the FA), you can firmly believe that with a little luck and the addition of a player or two, you might rise in just a few years to join the Premier League and maybe even make it to the Champions League in Europe.

In England, you can be sanguine about your club’s future. Perhaps someday American soccer will join the rest of the world and provide hope to all its citizens.

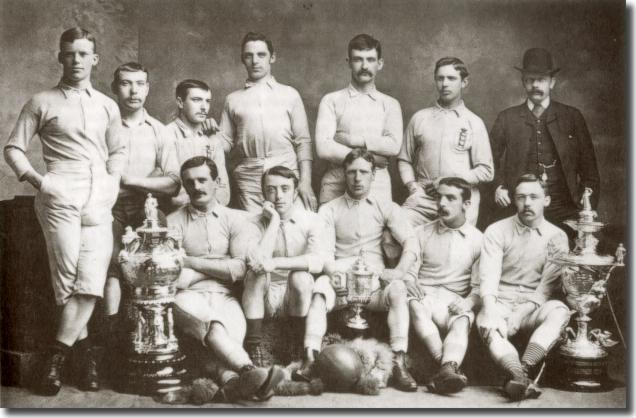

The image is of “Blackburn Olympic Football Club, … an English football club based in Blackburn, Lancashire, in the late 19th century. Although the club was only in existence for just over a decade, it is significant in the history of football in England as the first club from the north of the country and the first from a working-class background to win the country’s leading competition, the Football Association Challenge Cup (FA Cup). The cup had previously been won only by teams of wealthy amateurs from the Home counties, and Olympic’s victory marked a turning point in the sport’s transition from a pastime for upper-class gentlemen to a professional sport” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackburn_Olympic_F.C.). Don’t those fellows look sanguine?