Word of the Day: Progeny

Paul Schleifer

According to etymonline.com, progeny comes into English in the 14th century from Latin through French, but in a pretty unadulterated way. The 13th century French is progenie, and the Latin is progenies (“descendants,” “offspring,” “lineage,” “race,” “family”), from the stem of progignere (“beget”), from pro– (“forth”) + gignere (“to produce,” “to beget”). Gignere is from the PIE root *gene– (“to give birth,” “to beget”).

It should be pretty easy to see that there are a number of English words that go back to that PIE root *gene– and that relate to giving birth: “genes,” “genetics,” “genesis,” “eugenics,” “engender,” “congenital.” But even beyond those more obvious words, we can see “kin,” “kindred,” “kindergarten,” “kind,” and even “king.” We get those “k” words because of Grimm’s Law.

What is Grimm’s Law, and what’s the connection between the letter k and fairy tales?

The connection between Grimm’s Law and fairy tales is Jacob Grimm, one of the two Brothers Grimm of fairy tale fame. But that’s the only connection.

Jacob Grimm was a philologist and a linguist as well as a collector of folk tales.

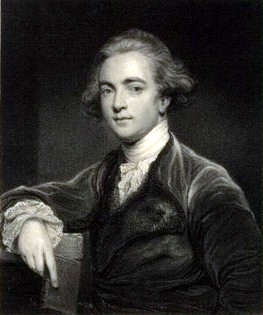

The story really starts with the linguistic prodigy Sir William Jones (1746-1794), who learned Greek, Latin, Persian, Arabic, and Hindu while in school. In addition to his linguistic studies, Jones was also a judge, and in 1783 he was appointed to a judgeship in Calcutta, India. He fell in love with Indian culture, started a journal called Asiatick Researches, and became proficient in Sanskrit. While earlier scholars had noted the similarities between Greek and Latin, Jones claimed that Greek and Latin were also related to Sanskrit, German, and Celtic.

In 1786, he gave a lecture (published in 1788) which included the following passage:

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Jones_(philologist)).

And thus began the study of the Indo-European family of languages.

But if these various languages are from the same family, how do we account for the differences? For instance, why do the Latins eat piscis while the English eat fish.

Jacob Grimm developed one theory to explain the differences, and it has been so thoroughly accepted that it is now known as Grimm’s Law. According to the law, certain consonant sounds in PIE developed in one way as the language became Latin but developed a different way in the Germanic languages.

According to Wikipedia,

Grimm’s law consists of three parts which form consecutive phases in the sense of a chain shift.[1] The phases are usually constructed as follows:

Proto-Indo-European voiceless stops change into voiceless fricatives.

Proto-Indo-European voiced stops become voiceless stops.

Proto-Indo-European voiced aspirated stops become voiced stops or fricatives

Thus the voiced velar plosive /g/ of PIE becomes the voiceless velar plosive /k/ of Germanic languages. So, the PIE root *gel– becomes the Latin gelū and English cold (German kalt, Faroese kaldur, etc.)

Thus we see how kin can be the progreny of gene.

The image is a portrait of Sir William Jones, a steel engraving by James Posselwhite, from the early 19th century. The original hangs in the Hall of University College, Oxford.