Word of the Day: Warlock

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Jim Butcher (IYKYK), is warlock. I have known this word for many, many years, but I never thought about it beyond what the standard accepted meaning is, but when I heard it while listening to a novel by Jim Butcher, I realized that I wanted to know more about the word.

Pronounced / ˈwɔrˌlɒk /, this noun means “a man who professes or is supposed to practice magic or sorcery; a male witch; sorcerer” or “a fortuneteller or conjurer” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/warlock). Merriam-Webster says, “a man practicing the black arts” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/warlock).

The word appears as “Middle English war-lou, from Old English wærloga ‘traitor, liar, enemy, devil,’ from wær ‘faith, fidelity; a compact, agreement, covenant,’ from Proto-Germanic *wera- (source also of Old High German wara ‘truth,’ Old Norse varar ‘solemn promise, vow’). This is reconstructed to be from PIE root *were-o- ‘true, trustworthy.’

“The second element is an agent noun related to leogan ‘to lie’ (see lie (v.1)). Compare Old English wordloga ‘deceiver, liar’).

“The original primary sense seems to have been ‘oath-breaker;’ it was given special application to the devil (c. 1000), but also used of giants and cannibals. The meaning ‘one in league with the devil’ is recorded from c. 1300.

“The ending in -ck (1680s) and the specific meaning ‘male equivalent of a witch’ (1560s) are from Scottish” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=warlock).

I’m not at all surprised that the application of the word to specifically male witches came from the Scots. During the English Renaissance and into the 18th century the Scots seemed particularly interested in witches. England’s James I, who before he became king of England was King James VI of Scotland, wrote a book about witches called Dæmonologie, In Forme of a Dialogue, Divided into three Books: By the High and Mightie Prince, James &c (1597), and many Shakespeare scholars that Macbeth was written in part to appeal to James’s interest in witches.

According to On This Day, on this date in 1775, the “British Parliament declares Massachusetts Colony in rebellion” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/february/9). I have actually seen February 11 given as the date for this, but it was a long time ago, so who can tell?

Many of us learned about some of the heroes of the American Revolution—Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Dr. Joseph Warren, and Crispus Attucks, not to mention George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. But one person you may not have heard of is Dr. Benjamin Church.

Born in 1734 in Rhode Island, Church went to Harvard and graduated when he was just 20 years old (although people went to college earlier in the 18th century than they do today). He apprenticed under a medical doctor before completing his medical studies in England, where he also met his wife. He returned to the colonies and set up his practice in Boston.

“Throughout the 1760s and 1770s, he emerged as a prominent Whig, or supporter of the American Revolution…. After the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, that killed several colonists, Church not only examined the body of Crispus Attucks, but he was also asked to give an oration on the anniversary of the event in 1773 in which he said:

Mankind apprized of their privileges, in being rational and free; in prescribing civil laws to themselves, had surely no intention of being enchained by any of their equals; and although they submitted voluntary adherents to certain laws for the sake of mutual security and happiness; they no doubt intended by the original compact, a permanent exemption of the subject body, from any claims, which were not expressly surrendered, for the purpose of obtaining the security and defense of the whole: Can it possibly be conceived that they would voluntarily be enslaved, by a power of their own creation?” (https://thelibertytrail.org/history/biographies/benjamin-church).

“His support for the Revolution continued when in 1774 he was elected to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and after the Revolution began, he was appointed to a committee “to consider what method is proper to take to supply the hospitals with surgeons and that the same gentlemen be a committee to provide medicine and other necessaries for hospitals”. In July 1775, the Continental Congress authorized the creation of a Medical Department with a Director General and Chief Surgeon. Dr. Benjamin Church was selected to serve as Director General, a role which ultimately made him the first Surgeon General of the United States” (ibid.).

However, while he was working with the colonists, he was also feeding information to General Gage, the British general in New York. “Church helped supply information including the location of arsenals for the Patriots. This communication continued until a letter was intercepted. After a trip to Philadelphia, Church attempted to send a ciphered letter to Gage through a series of messengers who were to transport the letter by boat to the British army and then to its intended recipient. However, Church’s first messenger in this chain, an old mistress, gave the letter to a Rhode Island baker and Patriot, Godfrey Wenwood. Instead of passing the letter along the chain, Wenwood instead gave the letter to General Nathanael Greene and it eventually made it to General George Washington. In October 1775, when the letter was decoded, it was found to contain information about Continental Troops before Boston as well as Church’s previous failed attempts to get Gage information, solidifying the evidence that Church was indeed a traitor in the eyes of Washington. Church was arrested and the matter was presented to the Continental Congress” (ibid.).

You might think that, after he was convicted (he confessed to sending the letters but not to treason, probably because he believed he was being loyal to the Crown), he would have been executed. That didn’t happen. After a brief period in jail, he was allowed to live at home until 1778, “when he was named in the Massachusetts Banishment Act, forcing those who supported the British or ‘joined the enemies thereof’ to leave the United States” (ibid.). He took a ship to the Caribbean, but that ship was lost at sea.

Along with the heroes of the Revolution, many of us have heard of the traitor Benedict Arnold, a man whose name has become a noun. But the first traitor of the American Revolution was actually Dr. Benjamin Church, a man who, though not known for using magic, might be described as a warlock.

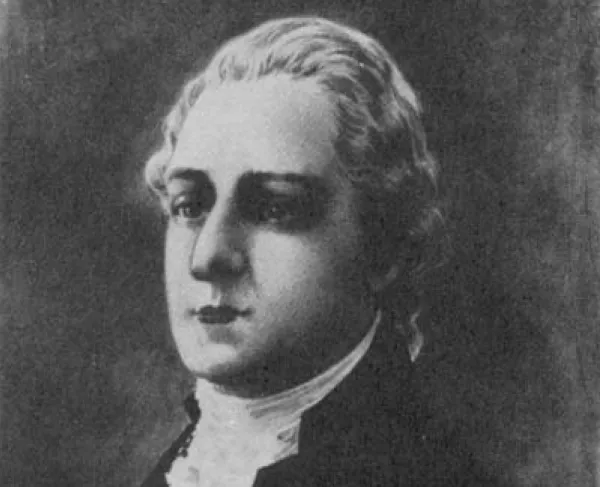

Today’s image is of Dr. Benjamin Church (https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/dr-benjamin-church).