Word of the Day: Invidious

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Word Guru, is invidious. Pronounced / ɪnˈvɪd i əs /, it’s an adjective that means “calculated to create ill will or resentment or give offense; hateful,” “offensively or unfairly discriminating; injurious,” or “causing or tending to cause animosity, resentment, or envy” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/invidious). Dictionary.com also lists “envious” as an obsolete synonym. Samuel Johnson, in his 1755 Dictionary, lists two definitions: 1. “Envious; malignant” and 2. “Likely to incur or to bring hatred,” after which he says, “This is the more usual sense” (https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/views/search.php?term=invidious).

It appears in English “c. 1600, from Latin invidiosus ‘full of envy, envious’ (also ‘exciting hatred, hateful’), from Invidia ‘envy, grudge, jealousy, ill will’ (see envy (n.)). Envious is the same word, but passed through French” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=invidious). Merriam-Webster explains in a little more detail, “Fittingly, ‘invidious’ is a relative of ‘envy.’ Both are descendants of ‘invidia,’ the Latin word for ‘envy,’ which in turn comes from invidēre, meaning ‘to look askance at’ or ‘to envy.’ (‘Invidious’ descends from ‘invidia’ by way of the Latin adjective invidiosus, meaning ‘envious,’ whereas ‘envy’ comes to English via the Anglo-French noun envie.) These days, however, ‘invidious’ is rarely used as a synonym for ‘envious.’ The preferred uses are primarily pejorative, describing things that are unpleasant (such as ‘invidious choices’ and ‘invidious tasks’) or worthy of scorn (‘invidious remarks’ or ‘invidious comparisons’)” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/invidious).

On this date in 1953, “General Fazlollah Zahedi arrests Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in a CIA-supported coup d’état” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/august/20).

The relationship between Iran and the West is one fraught with manipulation. At the beginning of the 20th century, the ruler of Iran sold petroleum interests to a British oil company; oil was indeed found in Iran, and at the beginning of World War I, Britain bought a controlling interest in the company. “In the aftermath of World War I there was widespread political dissatisfaction with the royalty terms of the British petroleum concession, under the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), whereby Persia received 16% of “net profits”. In 1921, after years of severe mismanagement under the Qajar dynasty, a coup d’état (allegedly backed by the British) brought a general, Reza Khan, into the government. By 1923, he had become prime minister, and gained a reputation as an effective politician with a lack of corruption. By 1925 under his influence, Parliament voted to remove Ahmad Shah Qajar from the throne, and Reza Khan was crowned Reza Shah Pahlavi, of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah began a rapid and successful modernization program in Persia, which up until that point had been considered to be among the most impoverished countries in the world” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1953_Iranian_coup_d’%C3%A9tat).

Reza Shah tried to balance the influence of the British, the Deutsch, and the Soviets, but once World War II broke out, the British and Soviets invaded Iran, without any Iranian resistance. “The primary reasons behind the Anglo-Soviet invasion was [sic] to remove German influence in Iran and secure control over Iran’s oil fields and the Trans-Iranian Railway in order to deliver supplies to the USSR. Reza Shah was deposed and exiled by the British to South Africa, and his 22-year-old son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was installed as the new Shah of Iran. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was supported by the Allies because they viewed him as being less able to act against their interests in Iran. The new Shah, unlike his father, was initially a mild leader and at times indecisive. During the 1940s he did not for most part take an independent role in the government, and much of Reza Shah’s authoritarian policies were rolled back. Iranian democracy effectively was restored during this period as a result” (ibid.).

After the war, the Brits left, but the Soviets stayed and tried to created two provinces that were satellites. Eventually, at the urging of the Americans, the Iranians drove the Soviets out, but a nationalist sentiment was growing. In 1949, after an assassination attempt, the Shah began to be more involved in politics. He revised the constitution, assembled the senate, and developed a loyal opposition, in particular a man named Mohammad Mosaddegh. Mosaddegh, who had been made a political prinsoner in 1940, was opposed to authoritarian rule and wanted to nationalize the oil industry (ibid.).

Mosaddega organized the opposition into The National Front, and he eventually became the prime minister. “The Shah and his new prime minister Mosaddegh had an antagonistic relationship. Part of the problem stemmed from the fact that Mosaddegh was connected by blood to the former royal Qajar dynasty, and saw the Pahlavi king as a usurper to the throne. But the real issue stemmed from the fact that Mosaddegh represented a pro-democratic force that wanted to temper the Shah’s rule in Iranian politics. He wanted the Shah to be a ceremonial monarch rather than a ruling monarch, thus giving the elected government power instead of the un-elected Shah. While the constitution of Iran gave the Shah the power to rule directly, Mosaddegh used the united National Front bloc and the widespread popular support for the oil nationalization vote (the latter which the Shah supported as well) in order to block the Shah’s ability to act” (ibid.).

But Mosaddegh gradually became more and more authoritarian. He also was pushing harder for nationalizing the oil industry in Iran. So the CIA decided that Mosaddegh had to go. “The Shah himself initially opposed the coup plans and supported the oil nationalization, but he joined in after being informed by the CIA that he too would be ‘deposed’ if he didn’t play along. The experience left him with a lifelong awe of American power and would contribute to his pro-US policies while generating a hatred of the British” (ibid.). So it happened, and for the next 25 years the Shah was supported by and supportive of the US. But while the Shah was won over, many in Iran objected to what they perceived as invidious actions by the CIA, and that perception would eventually lead to the deposition of the Shah.

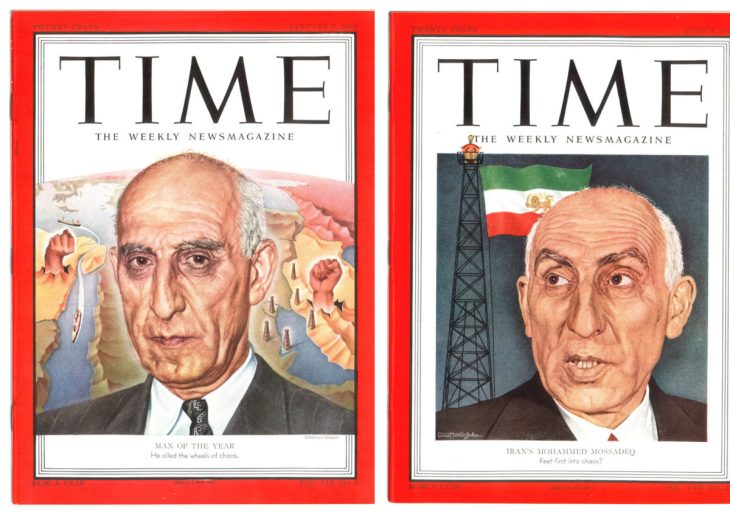

Today’s image is of Mohammad Mosaddegh on the cover of Time Magazine in 1951 and 1952, when he was named “Man of the Year” (https://www.genusfotografen.se/language/en/the-coup-against-mohammad-mosaddegh/).