Word of the Day: Adumbrate

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Word Guru’s daily email, is adumbrate. Dictionary.com offers two possible pronunciations, / æˈdʌm breɪt, / and / ˈæd əmˌbreɪt /, with the stress on the second syllable or the stress on the first syllable. I have only ever heard the second pronunciation, with the stress on the first syllable. The vowel sound in both pronunciations, / ʌ / and / ə /, are basically the same sound, but the first is found in a stressed syllable and the second, the schwa, is found in an unstressed syllable. The word is a verb that means “to produce a faint image or resemblance of; to outline or sketch,” “to foreshadow; prefigure,” or “to darken or conceal partially; overshadow” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/adumbrate).

Samuel Johnson, in his 1755 Dictionary, defines it as “To shadow out; to give a slight likeness; to exhibit a faint resemblance, like that which shadows afford of the bodies which they represent” (https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/views/search.php?term=adumbrate), so the meaning has stayed somewhat consistent for the last 270 years.

Etymonline.com says that the word entered the English language in the “1580s, ‘to outline, to sketch,’ from Latin adumbrates ‘sketched, shadowed in outline,’ also ‘feigned, unreal, sham, fictitious,’ past participle of adumbrare ‘cast a shadow over;’ in painting, ‘to represent (a thing) in outline,’ from ad ‘to’ (see ad-) + umbrare ‘to cast in shadow’ (from PIE root *andho- ‘blind; dark;’ see umbrage). The meaning ‘overshadow’ is from 1660s in English” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=adumbrate). In English it may be a backformation because adumbration appeared in English in the “1550s, ‘faint sketch, imperfect representation,’ from Latin adumbrationem (nominative adumbratio) ‘a sketch in shadow, sketch, outline,’ noun of action from past-participle stem of adumbrare ‘to cast a shadow, overshadow,’ in painting, ‘represent (a thing) in outline’” (ibid.).

Merriam-Webster seems to really like this word; it says, “Don’t throw shade our way if you’ve never crossed paths with adumbrate—the word’s shadow rarely falls across the pages of casual texts. It comes from the Latin word umbra, meaning ‘shadow,’ and is usually used in academic and political writing to mean ‘to foreshadow’ (as in ‘protests that adumbrated a revolution’) or ‘to suggest or partially outline’ (as in ‘a philosophy adumbrated in her early writings’). Adumbrate is a definite candidate for those oft-published lists of words you should know, and its relations range from the quotidian (umbrella) to the somewhat formal (umbrage) to the downright obscure (umbra). But it’s a word worth knowing, beyond a shadow of a doubt” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/adumbrate).

According to On This Day (https://www.onthisday.com/events/july/23), on this date in 1215, “Frederick II is crowned King of the Romans (King of the Germans) in Aachen.”

Frederick was born in 1194, the grandson of Frederick Barbarossa and the second son of Emperor Henry VI of the Hohenstaufen line. “Frederick was one of the most brilliant and powerful figures of the Middle Ages and ruled a vast area, beginning with Sicily and stretching through Italy all the way north to Germany. Viewing himself as a direct successor to the Roman emperors of antiquity, he was Emperor of the Romans from his papal coronation in 1220 until his death; he was also a claimant to the title of King of the Romans from 1212 and unopposed holder of that monarchy from 1215. As such, he was King of Germany, of Italy, and of Burgundy” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_II%2C_Holy_Roman_Emperor).

In addition to all that, “Frequently at war with the papacy, which was hemmed in between Frederick’s lands in northern Italy and his Kingdom of Sicily (the Regno) to the south, he was ‘excommunicated four times between 1227 and his own death in 1250’, [Jones, Dan (2019). Crusaders. UK: Head of Zeus. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-781-85889-9] and was often vilified in pro-papal chronicles of the time and after. Pope Innocent IV went so far as to declare him preambulus Antichristi (forerunner of the Antichrist)” (ibid.).

Frederick II of Hohenstauffen died around 55 years old, which by today’s standards is pretty young. He became a ruler at 21, which is way too young for anyone to have that kind of power over other people’s lives. He ruled over a lot of territory, which is too much power for any one person, in my humble opinion. So why am I writing about him today.

When I was in college, at Davidson, we had a two-year-long class called simply The Humanities. The class started with the ancient Egyptians (we read the original Sinbad stories), went into the Mesopotamians (The Epic of Gilgamesh), the Greeks, the Romans, and up into the 20th century. The focus was, clearly, on Western Civilization, but it wasn’t just history or literature. We looked at science, religion, philosophy, and even the fine arts. I really loved it because, I think, it fit in well with my way of thinking, which is to focus on synthesizing facts and ideas.

I cannot remember whether it was the 4th or 5th term (we were on a quarter system at DC), but in that particular term, my professor was Dr. McGeachy (pronounced / mək ‘gei hi /), a history professor who had attended Oxford, though I’m not sure when or for what degree. He was an elderly gentleman by that time (though, he was probably younger at that time than I am now), and he always wore his academic robe to class.

We had to write a term paper in his class, and on some certain day early in the term he handed out a mimeographed list of possible topics. He told us to go over the topics and pick one. At the end of class I put the list into my backpack and promptly forgot it.

Forgot it, that is, until I arrived in class one morning and heard Dr. McGeachy announce that it was time to turn in the sheet with our chosen topic. In a panic, I pulled the sheet out of my notebook, put my pencil down randomly, noted the topic, and circled it. No thought involved.

The topic I chose was, as I’m sure you’ve figured out, Frederick II of Hohenstauffen. Now, keeping in mind that this was approximately 50 years ago, it should come as no surprise that I have no idea what I wrote, what I said about Frederick. What I do remember is that I really enjoyed doing that paper. I had no prior interest in Frederick, and my paper on Frederick created in me no passion to study the Hohenstauffen dynasty or become a history major or make becoming King of the Romans my lifetime goal. But what it did do was teach me that almost any topic can be interesting, if you get far enough into it.

Maybe that paper adumbrated my later compiling a daily word of the day.

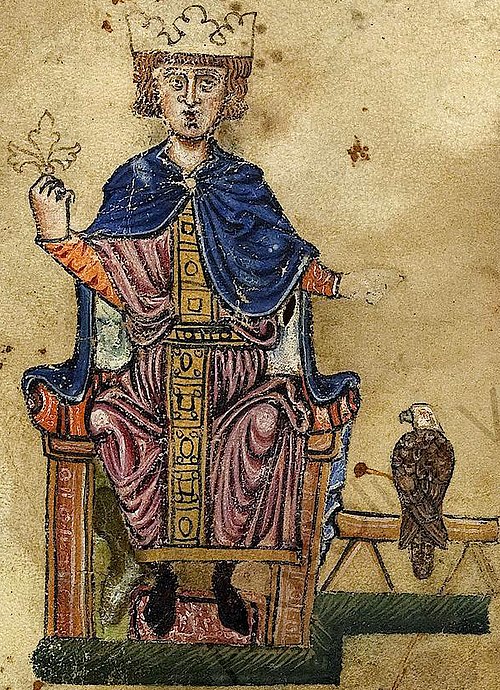

Today’s image is a “Contemporary portrait of Frederick II from the ‘Manfred manuscript’ (Biblioteca Vaticana, Pal. lat 1071) of De arte venandi cum avibus” (ibid.).