Word of the Day: Oscillate

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary), is oscillate. Pronounced / ˈɒs əˌleɪt /, with a secondary stress on the third syllable, oscillate means “to swing or move to and fro, as a pendulum does,” “to vary or vacillate between differing beliefs, opinions, conditions, etc.,” or two other meanings that are similar but specific to certain academic disciplines (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/oscillate).

According to Etymonline.com, the word entered the English language in “1726, intransitive, ‘to vibrate, move backward and forward,’ as a pendulum does, a back-formation from oscillation, or else from Latin oscillatus, past participle of oscillare ‘to swing.’ Transitive sense of ‘cause to swing backward and forward’ is by 1766. From 1917 in electronics, ‘cause oscillation in an electric current’” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/oscillate). As a reminder, a backformation is a word that is derived from a longer word, derived from what appears to be a suffix (usually) that would normally change a word from one category to another. So, we have a verb like contract, and we add the –ion to get the noun contraction. But in this case, the word oscillation preceded the word oscillate in English, which entered the language in the 1650s.

According to On This Day, on this date in 1894, “2000 fed troops recalled from Chicago, having ended Pullman strike” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/july/20).

The Pullman Company made cars for railroads. The founder and owner, George Pullman, came up with the idea for manufacturing railroad cars after a long, uncomfortable ride on somebody else’s car. He created luxury cars with sleeping births. In 1880, after the great railroad strike of 1877, Pullman announced that he was building the town of Pullman, Illinois, in order to attract a higher quality employee and provide a better work experience. “Many critics praised Pullman’s concept and planning. One newspaper article titled ‘The Arcadian City: Pullman, the Ideal City of the World’ praised the town as ‘the youngest and most perfect city in the world, Pullman; beautiful in every belonging.’ In February 1885, Harper’s Monthly published an article by Richard T. Ely entitled ‘Pullman: A Social Study’. Though the article offered praise for creating an elevated environment for its workers, it criticized the all-encompassing influence of the company ultimately concluding that ‘Pullman is un-American’ and benevolent, well-wishing feudalism’” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pullman_Company).

Like many company towns, the company provided housing, food, and other supplies, but not for free. Houses and flats were for rent. Supplies were for purchase at the company store. The company set the prices. It was perfectly legal for employees to travel to a nearby town to purchase food and other things, but the company store was just steps away, so it was more convenient. This deal worked out okay for some years.

The Panic of 1893 was the most serious economic depression before the Great Depression that came 36 years later. On May 5, 1893, the stock market fell 24%, the largest single-day drop until the Crash of ’29. The causes were numerous: a bank crisis in Australia, failing investments and failing crops in Argentina and Brazil, a bubble in the train car market, the Tariff Act of 1890 and others. One result of the panic was a drop in orders for new railcars. In response to the drop in orders, George Pullman laid off a percentage of his Pullman workers, and for the ones who were laid off, he cut their wages.

But in Pullman, Illinois, he did not cut rent or the price of goods sold in the company stores. The Merle Travis song “Sixteen Tons” was written half a century later about a coal mine company’s town, but it might reflect the problem: “You load 16 tons, what do you get? / Another day older and deeper in debt / St. Peter, don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go / I owe my soul to the company store” (https://www.musixmatch.com/lyrics/Tennessee-Ernie-Ford/Sixteen-Tons).

“The employees filed a complaint with the company’s owner, George Pullman. Pullman refused to reconsider and even dismissed the workers who were protesting. The strike began on May 11, 1894, when the rest of his staff went on strike. This strike would end by the president sending U.S. troops to break up the scene” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pullman_Strike).

“Many of the Pullman factory workers joined the American Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene V. Debs, which supported their strike by launching a boycott in which ARU members refused to run trains containing Pullman cars. At the time of the strike approximately 35% of Pullman workers were members of the ARU. The plan was to force the railroads to bring Pullman to compromise. Debs began the boycott on June 26, 1894. Within four days, 125,000 workers on twenty-nine railroads had “walked off” the job rather than handle Pullman cars. The railroads coordinated their response through the General Managers’ Association, which had been formed in 1886 and included 24 lines linked to Chicago. The railroads began hiring replacement workers (strikebreakers), which increased hostilities. Many African Americans were recruited as strikebreakers and crossed picket lines, as they feared that the racism expressed by the American Railway Union would lock them out of another labor market. This added racial tension to the union’s predicament” (ibid.). Quite a mess, eh?

The president at the time was Grover Cleveland. Cleveland was the first Democrat to be elected president after the Civil War, and he was the first person elected to non-consecutive terms, occupying the White House from 1885 to 1889 and 1893 to 1897 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grover_Cleveland). In his first term, he signed the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, making the railroad industry subject to federal regulation. When Debs and the ARU began to strike against Pullman and, by extension, the railroad industry, Cleveland acted. He first got a federal judge to enact an injunction against the strikers, and when the strikers ignored the injunction, he sent in the troops. “’If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postcard in Chicago’, he proclaimed, ‘that card will be delivered.’ Most governors supported Cleveland except Democrat John P. Altgeld of Illinois, who became his bitter foe in 1896. Leading newspapers of both parties applauded Cleveland’s actions, but the use of troops hardened the attitude of organized labor toward his administration” (ibid.).

“Federal forces broke the ARU’s attempts to shut down the national transportation system city by city. Thousands of US Marshals and 12,000 U.S. Army troops, led by Brigadier General Nelson Miles, took part in the operation. After learning that President Cleveland had sent troops without the permission of local or state authorities, Illinois Governor John Altgeld requested an immediate withdrawal of federal troops. President Cleveland claimed that he had a legal, constitutional responsibility for the mail; however, getting the trains moving again also helped further his fiscally conservative economic interests and protect capital, which was far more significant than the mail disruption. His lawyers argued that the boycott violated the Sherman Antitrust Act, and represented a threat to public safety. The arrival of the military and the subsequent deaths of workers in violence led to further outbreaks of violence. During the course of the strike, 30 strikers were killed and 57 were wounded” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pullman_Strike). And Grover Cleveland broke the railroad strike.

What we had in 1894 was a Democratic president sending in federal troops without the permission of the state governor, leading to some violence and the squelching of the workers’ rights. More recently, a Republican president sent federal troops to a state without the permission of that state’s governor, leading to some violence and perhaps the squelching of people’s rights. In one case, the new media supported the president. In the other case, the news media opposed the president. Funny how we as a people oscillate.

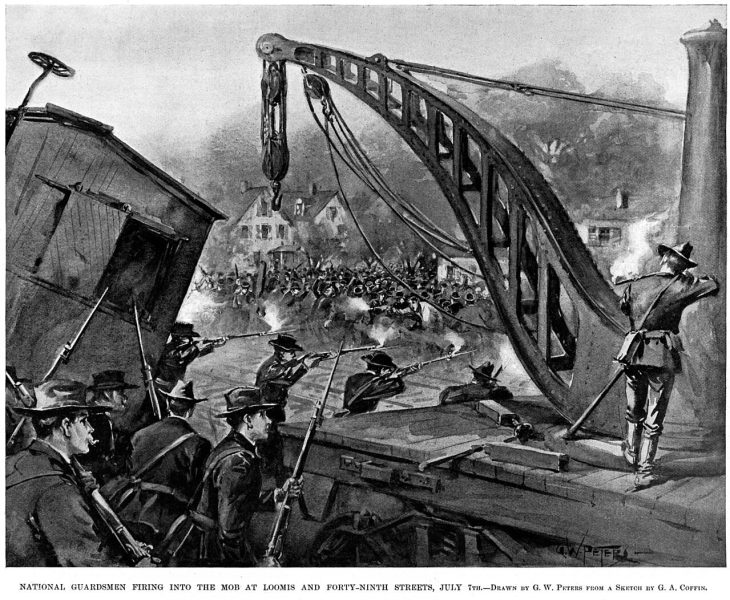

Today’s image is a “Depiction of Illinois National Guardsmen firing at striking workers on July 7, 1894, the day of greatest violence by G.W. Peters, from a sketch by G.A. Coffin. – Published in Harpers Weekly, vol. 38, whole no. 1961 (July 21, 1894), pg. 689” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pullman_Strike#/media/File:940707-gwpeters-nationalguardfiring-harpers-940721.jpg).