Word of the Day: Bellicose

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary) is bellicose. Bellicose, pronounced / ˈbɛl ɪˌkoʊs /, is an adjective that means “inclined or eager to fight; aggressively hostile” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/bellicose). Merriam-Webster defines it as “favoring or inclined to start quarrels or wars” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bellicose), which gives it more of a macro feel.

M-W adds to that sense, “Since bellicose describes an attitude that hopes for actual war, the word is generally applied to nations and their leaders. In the 20th century, it was commonly used to describe such figures as Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm, Italy’s Benito Mussolini, and Japan’s General Tojo, leaders who believed their countries had everything to gain by starting wars. The international relations of a nation with a bellicose foreign policy tend to be stormy and difficult, and bellicosity usually makes the rest of the world very uneasy” (ibid.).

Etymonline.com says that the word first appears in English in the “early 15c., ‘inclined to fighting,’ from Latin bellicosus ‘warlike, valorous, given to fighting,’ from bellicus ‘of war,’ from bellum ‘war’ (Old Latin duellum, dvellum), which is of uncertain origin. The best etymology for duellum so far has been proposed by Pinault 1987, who posits a dim. *duelno- to bonus. If *duelno- meant ‘quite good, quite brave’, its use in the context of war (bella acta, bella gesta) could be understood as a euphemism, ultimately yielding a meaning ‘action of valour, war’ for the noun bellum. [de Vaan]” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/bellicose).

According to On This Day, on this date in 1890, “Cecil Rhodes’ colonists attack Motlousi in Matabeleland” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/june/27).

Matabeleland is, currently, an area of southern Zimbabwe. This area of Africa was conquered by Bantu speaking people and then by Nguni. It was formed into a militaristic and strong centralized state, and Matabeleland was formally founded in 1840. The Boer government of South Africa made a treaty with the king, Mzilikazi. But in 1867, gold was discovered in the area, and of course the British became interested (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matabeleland). “Mzilikazi died on 9 September 1868, near Bulawayo. His son, Lobengula, succeeded him as king. In exchange for wealth and arms, Lobengula granted several concessions to the British, but it was not until twenty years later that the most prominent of these, the 1888 Rudd Concession gave Cecil Rhodes exclusive mineral rights in much of the lands east of Lobengula’s main territory. Gold was already known to exist, but with the Rudd concession, Rhodes was able in 1889 to obtain a royal charter to form the British South Africa Company” (ibid.).

“In 1890, Rhodes sent a group of settlers, known as the Pioneer Column, into Mashonaland where they founded Fort Salisbury (now Harare). In 1891 an Order-in-Council declared Matabeleland and Mashonaland British protectorates. Rhodes had a vested interest in the continued expansion of white settlements in the region, so now with the cover of a legal mandate, he used a brutal attack by Ndebele against the Shona near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) in 1893 as a pretext for attacking the kingdom of Lobengula” (ibid.).

Cecil Rhodes was born in Hertfordshire, England to a Church of England cleric. He was unhealthy as a child; his family feared he might have tuberculosis, so he was sent to South Africa for the climate. After failing at farming, the 18-year-old Rhodes and his older brother got interested in diamond mining. Soon, he and his business partners had a monopoly, having bought up the other diamond mining companies in the area (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_Rhodes).

Rhodes attended Oxford University in an on-and-off manner: “In 1873, Rhodes left his farm field in the care of his business partner, Rudd, and sailed for England to study at university. He was admitted to Oriel College, Oxford, but stayed for only one term in 1874. He returned to South Africa and did not return for his second term at Oxford until 1876. He was greatly influenced by John Ruskin’s inaugural lecture at Oxford, which reinforced his own attachment to the cause of British imperialism” (ibid.).

In addition to being a successful business person, Rhodes also entered politics. “In 1890, Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. He introduced various Acts of Parliament to push black people from their lands and make way for industrial development. Rhodes’s view was that black people needed to be driven off their land to ‘stimulate them to labour’ and to change their habits. ‘It must be brought home to them’, Rhodes said, ‘that in future nine-tenths of them will have to spend their lives in manual labour, and the sooner that is brought home to them the better’” (ibid.).

“Rhodes used his wealth and that of his business partner Alfred Beit and other investors to pursue his dream of creating a British Empire in new territories to the north by obtaining mineral concessions from the most powerful indigenous chiefs. Rhodes’ competitive advantage over other mineral prospecting companies was his combination of wealth and astute political instincts, also called the ‘imperial factor,’ as he often collaborated with the British Government” (ibid.). In other words, he employed what today we might call crony capitalism or state capitalism, exploited the people who were native to that land, and became wealthy and powerful.

If the last name sounds familiar, there might be a reason: “In his last will, he provided for the establishment of the Rhodes Scholarship…. The scholarship enabled male students from territories under British rule or formerly under British rule and from Germany to study at Rhodes’s alma mater, the University of Oxford. Rhodes’ aims were to promote leadership marked by public spirit and good character, and to ‘render war impossible’ by promoting friendship between the great powers” (ibid.).

I have to admit that I find the noble sounding spirit of the description of the Rhodes scholarship to be ironic given how Cecil Rhodes became wealthy. For many of us who attended upper tier colleges or universities, the Rhodes Scholarship was a symbol of accomplishment. Having learned about Cecil John Rhodes, I’m glad I didn’t receive one. Being bellicose is bad enough; being bellicose for personal profit seems even worse.

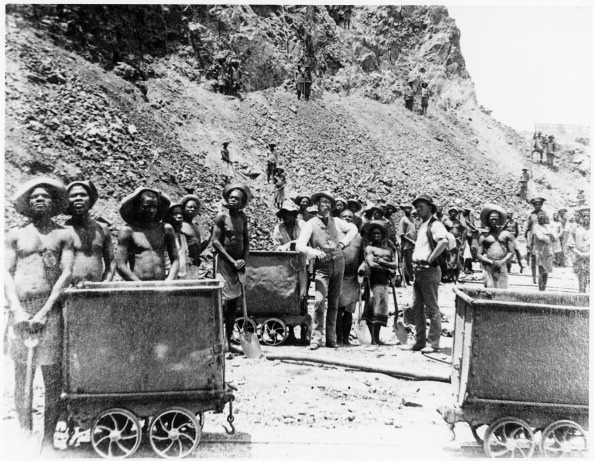

Today’s image is “Zulu workers at De Beers diamond mines, Kimberley, South Africa, c1885. In 1887 and 1888 Cecil Rhodes amalgamated the diamond mines around Kimberley, which included De Beers, into Consolidated Mines. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images) (https://100r.org/2014/05/rough-and-polished/).