Word of the Day: Dudgeon

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary), is dudgeon. Dudgeon, pronounced / ˈdʌdʒ ən / (the ʌ in the first syllable is basically the same as the schwa in the second syllable except that the schwa is never found in a stressed syllable), is a noun that means, “a feeling of offense or resentment; anger” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/dudgeon). Merriam-Webster gives this as its second definition: “a fit or state of indignation—often used in the phrase in high dudgeon” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dudgeon). For its first definition, M-W says that it means “a wood used especially for dagger hilts” or “a haft made of dudgeon” or “a dagger with a handle of dudgeon”; the first M-W calls “obsolete” and the last “archaic” (ibid.).

Etymonline.com starts with the definition “’feeling of offense, resentment, sullen anger’” and says that the word appears in the English language in the “1570s, duggin, of unknown origin. One suggestion is Italian aduggiare ‘to overshadow,’ giving it the same sense development as umbrage. No clear connection to earlier dudgeon (late 14c.), a kind of wood used for knife handles, which is perhaps from French douve ‘a stave,’ which probably is Germanic. The source also has been sought in Celtic, especially Welsh dygen ‘malice, resentment,’ but OED reports that this ‘appears to be historically and phonetically baseless’” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/dudgeon). So the one word for which M-W gives two different definitions is actually two different words, both with uncertain etymologies.

The entry says that dudgeon has the “same sense development as umbrage,” so let’s take a look at umbrage, another rarely used word in contemporary English: it first appears in English in the “early 15c., ‘shadow, darkness, shade’ (senses now obsolete), from Old French ombrage ‘shade, shadow,’ from noun use of Latin umbraticum ‘of or pertaining to shade; being in retirement,’ neuter of umbraticus ‘of or pertaining to shade,’ from umbra ‘shade, shadow,’ from PIE root *andho- ‘blind; dark’ (source also of Sanskrit andha-, Avestan anda- ‘blind, dark’). Especially shade from the foliage of trees. The word had many figurative uses in 17c.; the meaning ‘suspicion that one has been slighted,’ is recorded by 1610s from the notion of being ‘overshadowed’ by another and consigned to obscurity. Hence phrase take umbrage at, attested by 1670s. Compare modern (by 2013) slang verbal phrase throw shade ‘(subtly) insult (something or someone)’” (ibid.). And in case you’re wondering, yes, umbrage is related to umbrella, which comes from a Latin diminutive of the Latin umbra, meaning “shade, shadow.” In Mediterranean countries, an umbrella is used for shade while in England it is used for protection from rain.

On this date in 1917, according to On This Day, Ernie Shore accomplished one of the rarest feats in Major League Baseball history.

Shore was born in North Carolina, played his college baseball for Guilford College, and eventually was signed by the Baltimore Orioles, a AA team at that time. Because of financial difficulties, the Orioles sold Shore, Ben Egan, and a kid named Babe Ruth to the Boston Red Sox. As a Red Sox pitcher, Shore helped lead the team to consecutive World Series victories in 1915 and 1916 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernie_Shore). Shore would miss the 1918 season because of World War I, and his career was cut short due to injury; he retired from the game in 1921. He moved back to the Winston-Salem, NC, area, and was eventually elected sheriff of Forsyth County, an office he held until 1970. He died 10 years later (ibid.).

But it was in 1917 that he pulled off the incredible.

Babe Ruth, who was, at that time, a pitcher for the Red Sox, started the first of a double header against the Washington Senators. Things went downhill very quickly.

“’Ball,’ yelled umpire Brick Owens, earning a glare from Ruth, who entered the game with a 12-4 record and complete games in his previous seven starts.

Three more pitches drew the same call, and the Babe’s irritation grew with each. As Morgan took his free pass to first base, Ruth continued jawing with Owens, according to Boston Globe sportswriter Edward F. Martin.

‘Get in there and pitch,’ the umpire ordered.

‘Open your eyes and keep them open,’ Ruth yelled.

‘Get in and pitch or I will run you out of there,’ Owens warned.

‘You run me out and I will come in and bust you on the nose,’ the Babe replied.1

Owens and Ruth stayed true to their words. Owens ejected Ruth, and Ruth charged the plate to throw a pair of punches. The Babe’s left missed, but his right hook glanced off Owens’ mask, landing behind the umpire’s left ear. Team benches cleared, and the ensuing scrum prompted players and Red Sox player-manager Jack Barry to drag Ruth off the field” (https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-23-1917-bostons-babe-ruth-and-ernie-shore-combine-to-no-hit-senators/).

With Ruth gone, the Red Sox manager called on Ernie Shore to come in. Shore took the mound with very little chance to warm up. With Shore’s first pitch, Ray Morgan, the man who got the walk to start the game, decided to try to steal second base. He was thrown out.

After that, Shore retired 26 straight batters, and the Red Sox won the game 4-0.

In baseball, if a starting pitcher records 27 straight outs and nobody on the other team reaches first by any means, we call that a perfect game. In 154 years of MLB history, only 24 perfect games have been thrown. The only achievement in major league baseball that is rarer than a perfect game is a natural cycle, which has been achieved only 14 times in 154 years. Hitting for the cycle means getting a single, a double, a triple, and a home run all in the same game, and it has been done well over 300 times (still pretty unusual). But a natural cycle is when the hitter gets those hits in that order.

Ernie Shore pitched a perfect game, and that is how it went into the record books. But in 1991, MLB changed the definition of a perfect game, and because Ray Morgan walked to start the game, Shore’s effort was downgraded to a no hitter. In fact, he didn’t even get credit for a no hitter by himself. Officially, Babe Ruth and Ernie Shore pitched a combined no hitter. That’s still quite an accomplishment since the record books show only 326 official no hitters, combined or otherwise, in the history of the majors, but it’s not the same as a perfect game.

Babe Ruth was in high dudgeon when he was tossed by Brick Owens after just four pitches, all called balls. But I think Ernie Shore deserves to be in high dudgeon for not getting credit for one of the most remarkable feats in the history of the game. Then again, he had been gone for more than a decade when the rule was changed.

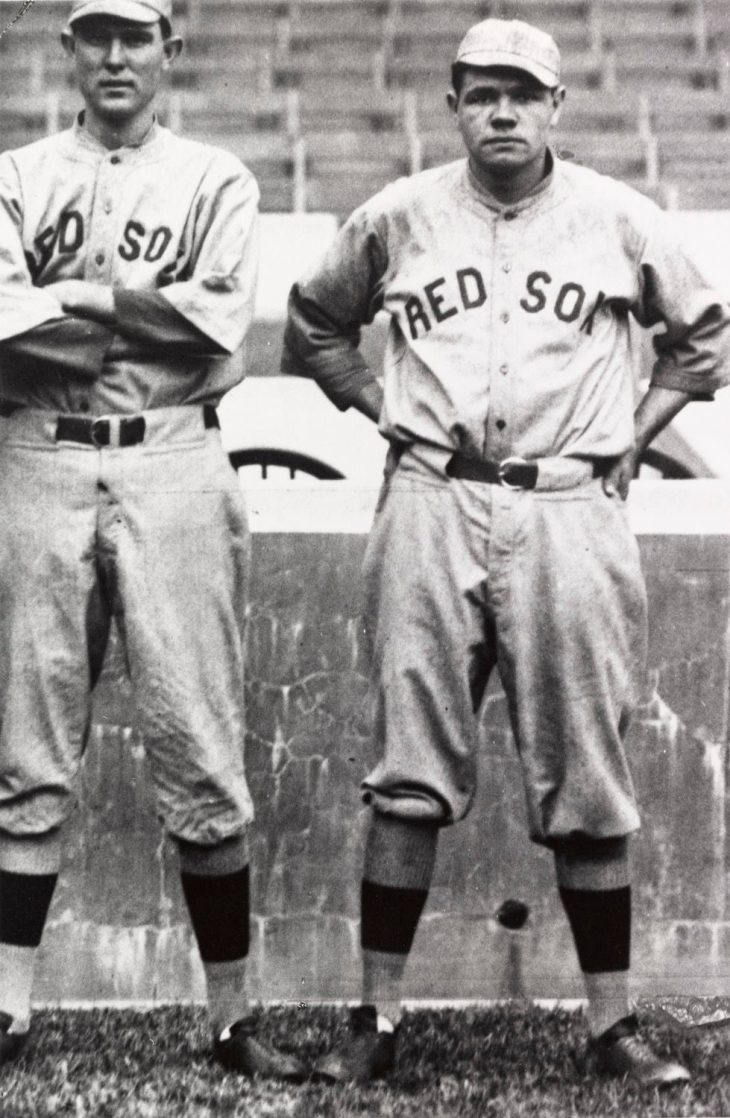

Today’s image is a photo of Ernie Shore, on the left, and Babe Ruth (https://baseballhall.org/discover/babe-ruth-made-history-with-help-from-ernie-shore).