Word of the Day: Nondescript

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary), is nondescript. Nondescript is an adjective meaning “of no recognized, definite, or particular type or kind” or “undistinguished or uninteresting; dull or insipid” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/nondescript). It’s pronounced /ˌnɒn dɪˈskrɪpt/ (ibid.); note that the emphasis is on the last syllable, with a secondary emphasis on the prefix. But at the same time the first syllable’s vowel is not a schwa, but I can imagine that some people would pronounce it /də/.

Merriam-Webster says, “It is relatively easy to describe the origins of nondescript (and there’s a hint in the first part of this sentence). Nondescript was formed by combining the prefix non- (meaning ‘not’) with descriptus, the past participle of the Latin verb describere, meaning ‘to describe.’ It is no surprise, then, that when the word was adopted in the late 17th century by English speakers, it was typically applied to something (such as a genus or species) that had not yet been described” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/nondescript).

Etymonline.com says that the word first appeared in English in the “ 1680s, in scientific use, ‘not hitherto described’ (a sense now obsolete), coined from non- ‘not’ + Latin descriptus, past participle of describere ‘to write down, copy; sketch, represent’ (see describe). The general sense of ‘not easily described or classified,’ hence ‘of no particular kind,’ is from 1806” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/nondescript). The website then gives the etymology of describe, that it entered the language in the “mid-13c., descriven, ‘interpret, explain,’ a sense now obsolete; c. 1300, ‘represent orally or by writing,’ from Old French descrivre, descrire (13c.) and directly from Latin describere ‘to write down, copy; sketch, represent,’ from de ‘down’ (see de-) + scribere ‘to write’ (from PIE root *skribh- ‘to cut’).

From late 14c. as ‘form or trace by motion;’ c. 1400 as ‘delineate or mark the form or figure of, outline.’ Reconstructed with Latin spelling from c. 1450” (ibid.). This business of reconstructed spellings happened with a number of English words over the years, most notably debt, which entered English from Old French dete, but was changed to debt because the Latin root was debitum despite the fact that no English speaker ever in the history of the language ever tried to pronounce that b in the English word.

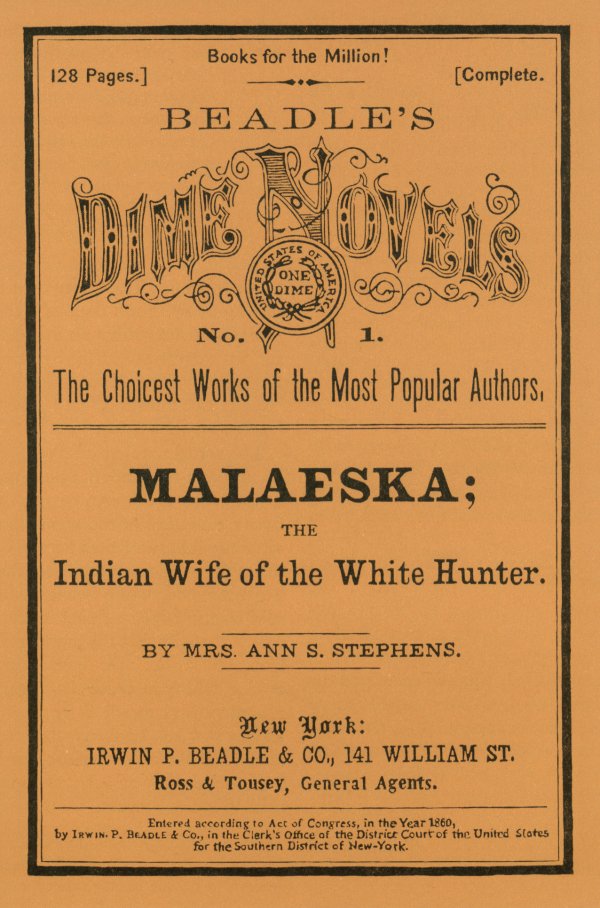

This date in 1860 saw the “First US ‘dime novel’ published, ‘Malaeska, The Indian Wife of the White Hunter,’ by Mrs. Ann S. Stephens” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/june/9).

Ann S. Stephens (1810-1886) wanted to be a writer from an early age. After she married Edward Stephens, the couple moved to Portland, ME, and founded the Portland Magazine, a magazine for women. A few years later they moved to New York City where she became associate editor of Ladies’ Companion, and then moved to Graham’s Magazine, and then to Peterson’s Magazine. “In 1856 she founded her own magazine, Mrs. Stephens’ Illustrated New Monthly, but in 1858 it was merged with Peterson’s” (https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ann-Sophia-Stephens). While she was working with these various magazines, she was also submitting her own work, “with her melodramatic romances and histories often appearing in serial form” (ibid.).

Malaeska, The Indian Wife of the White Hunter was serialized in the Ladies’ Companion in February, March, and April of 1839 (https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7504361-malaeska). The novel “tells the story of Malaeska, a Native American woman who falls in love with a white hunter named Jasper Western. Despite the cultural differences and prejudices of the time, the two marry and have a child together. However, their happiness is short-lived as Jasper is killed, leaving Malaeska to raise their child alone. The novel explores themes of love, loss, and cultural clashes in the early American frontier” (https://www.amazon.com/Malaeska-Indian-Wife-White-Hunter/dp/1436684072).

In 1860, “Erastus and Irwin Beadle released a new series of cheap paperbacks, Beadle’s Dime Novels” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dime_novel), and they chose to reprint Malaeska as the first number in the series. “It sold more than 65,000 copies in the first few months after its publication as a dime novel. Dime novels varied in size, even in the first Beadle series, but were mostly about 6.5 by 4.25 inches (16.5 by 10.8 cm), with 100 pages. The first 28 were published without a cover illustration, in a salmon-colored paper wrapper. A woodblock print was added in issue 29, and the first 28 were reprinted with illustrated covers. The books were priced, of course, at ten cents” (ibid.). Soon other publishers followed suit.

According to Rachel Rosenberg of Book Riot, “At a cost of 5–15¢ each, reading wasn’t just for the aristocracy anymore. The price helped the books into the hands of the working class; before this, regular books sold for $1–1.50, which was completely unaffordable for them.

“Their pages were filled with formulaic-if-enthralling tales of rollicking adventures. Their short length—the books were printed on cheap, lightweight paper—helped to get them into people’s hands (and back pockets). In the beginning, they were especially popular with bored Civil War soldiers, many of whom read the books during mundane moments at camp” (https://bookriot.com/dime-novels/).

Rosenberg also says, “The history of dime novels tells the story of how cheap books led to increased literacy in the working classes,” but this is a bit of a chicken-and-egg issue. Had the literacy rate not increased among the working class, the dime novel would have had no customers. And in truth neither the increased literacy rate nor the growing supply of cheap reading material could have happened had it not been for the Industrial Revolution, which created jobs that paid better than the farm jobs that were the norm before the IR.

Rosenberg also says, “Until I began researching this post, I thought dime novels were the same thing as pulp fiction (false)” (ibid.). But the mistake is not all that surprising given the reception of dime novels among the elites: “the quality of the fiction was derided by highbrow critics, and the term dime novel came to refer to any form of cheap, sensational fiction, rather than the specific format” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dime_novel).

Ann S. Stephens, the Beadles, and the dime novel should be remembered for creating a broader interest in reading. My own experience tells me that young readers improve their reading skills by reading, not necessarily only by reading the classics. And almost anything that helps a young reader practice the skill of reading is worthwhile, even if the cover and the contents are somewhat nondescript.

Today’s image is, of course, the cover of the first of Beadles’ Dime Novels, Malaeska, The Indian Wife of the White Hunter (https://athrillingnarrative.com/2012/10/20/yellow-back-gold/).