Word of the Day: Longueurs

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary), is longueur. Longueur is a noun, pronounced /lɔŋˈgɜr, lɒŋ-/, that means “a long and boring passage in a literary work, drama, musical composition, or the like” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/longueur)

Merriam-Webster says, “You’ve probably come across long, tedious sections of books, plays, or musical works before, but perhaps you didn’t know there was a word for them. English speakers began using the French borrowing longueur in the late 18th century. As in English, French longueurs are tedious passages, with longueur itself literally meaning ‘length.’ An early example of longueur used in an English text is from 18th-century writer Horace Walpole, who wrote in a letter, ‘Boswell’s book is gossiping; . . . but there are woful longueurs, both about his hero and himself’” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/longueur).

Longueur is a straight borrowing from French, and the passage quoted above is, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (https://www.oed.com/dictionary/longueur_n?tl=true) is the first time the word appears in English. According to the Alpha Dictionary website, the word “started out as PIE dlon-gho-/dlen-gho- ‘long/length’, origin of English long, Dutch and German lang ‘long’ and Latin longus ‘long’. French inherited the Latin word, reduced it to long, extended it to the noun longue, and added the French suffix –eur, to get longueur ‘length, long time’. Why the initial D in the PIE root? Because in Russian the words for ‘long’ are dlinnyi (space) and dolgii (time), and in Greek the word is dolikos. English linger was in Old English lengan ‘to prolong’, another descendant of the E variant of the PIE word for ‘long’” (https://www.alphadictionary.com/goodword/word/longueur).

You might wonder why Walpole didn’t just write “but there are woeful long boring passages, about….” So here’s my theory. The upper class in England spoke both English and French (and perhaps still do) from the Middle Ages onward. French was the prestige language among the rich not only in England but throughout Europe, just as Latin was the prestige language among the educated. So using French words probably came somewhat naturally to Walpole even though there were English words. But the fact that he used longueurs in this specific way suggests that the French word, with this specific mean, was already current among his peers. Otherwise, he would have had to explain himself. Thus while his letter is the first evidence of its usage, the word was probably being used in this particular way before Walpole put it down in his letter.

On this date in 1949, according to On This Day (https://www.onthisday.com/events/june/8), “Secker & Warburg publishes George Orwell‘s seminal novel ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’, set in the totalitarian state of Oceania.”

I’m going to assume that you already know the basic plot of 1984. If you don’t, I wouldn’t want to spoil it for you, and I would encourage you to read it or at least put it on your TBR list. I just want to point out how observant Orwell was about the relationship between language and political control. One of the inventions of 1984 was Newspeak. The wiki on Newspeak says, “To meet the ideological requirements of Ingsoc (English Socialism) in Oceania, the Party created Newspeak, which is a controlled language of simplified grammar and limited vocabulary designed to limit a person’s ability for critical thinking. The Newspeak language thus limits the person’s ability to articulate and communicate abstract concepts, such as personal identity, self-expression, and free will, which are thoughtcrimes, acts of personal independence that contradict the ideological orthodoxy of Ingsoc collectivism” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newspeak). The idea of Newspeak came from “Basic English (British American Scientific International Commercial English), which was proposed by the British linguist Charles Kay Ogden in 1930. As a controlled language without complex constructions or ambiguous usages, Basic English was designed to be easy to learn, to sound, and to speak, with a vocabulary of 850 words composed specifically to facilitate the communication of facts, not the communication of abstract thought. While employed as a propagandist by BBC during the Second World War (1939–1945), Orwell grew to believe that the constructions of Basic English, as a controlled language, imposed functional limitations upon the speech, the writing, and the thinking of the users” (ibid.).

Newspeak, while reducing the total number of words available to speakers of the new English language, does introduce words. For instance, thoughtcrime “describes the personal beliefs that are contrary to the accepted norms of society” (ibid.). Facecrime refers to “a facial expression which reveals that one has committed thoughtcrime” (ibid.).

One of my favorite terms from 1984 is duckspeak. In the appendix entitled “The Principles of Newspeak,” Orwell writes, “Ultimately it was hoped to make articulate speech issue from the larynx without involving the higher brain centres at all. This aim was frankly admitted in the Newspeak word duckspeak, meaning ‘to quack like a duck’ (http://www.orwelltoday.com/duckspeak.shtml). In Chapter 5 of the novel, there is this exchange:

“Winston turned a little sideways in his chair to drink his mug of coffee. At the table on his left the man with the strident voice was still talking remorselessly away….He held some important post in the FICTION DEPARTMENT….It was just a noise, a quack-quack-quacking….Every word of it was pure orthodoxy, pure Ingsoc….Winston had a curious feeling that this was not a real human being but some kind of dummy. It was not the man’s brain that was speaking, it was his larynx. The stuff that was coming out of him consisted of words, but it was not speech in the true sense: it was noise uttered in unconsciousness, like the quacking of a duck.

“Syme had fallen silent for a moment, and with the handle of his spoon was tracing patterns in the puddle of stew. The voice from the other table quacked rapidly on, easily audible in spite of the surrounding din.

“’There is a word in Newspeak’ said Syme, ‘I don’t know whether you know it: duckspeak, to quack like a duck. It is one of those interesting words that have two contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent, it is abuse: applied to someone you agree with, it is praise’” (ibid.)

If you think about it, there are a lot of new words being used in our society all the time, many of them made up for one particular group or another. But then there are also words that are coined for the sake of political advantage, and if you think long enough you can probably come up with some of them, too. But I’m not a pessimist. I don’t really agree with Orwell that a totalitarian government can restrict the thoughts of people by restricting their speech. We not only invent new words but also borrow words, and in that borrowing we can keep ideas alive, even ones that are contrary to political correctness however that may look.

And like Winston, our thoughts wander through the longueurs of the speeches of those who wish to control our very thoughts because we recognize the quacking as they do it.

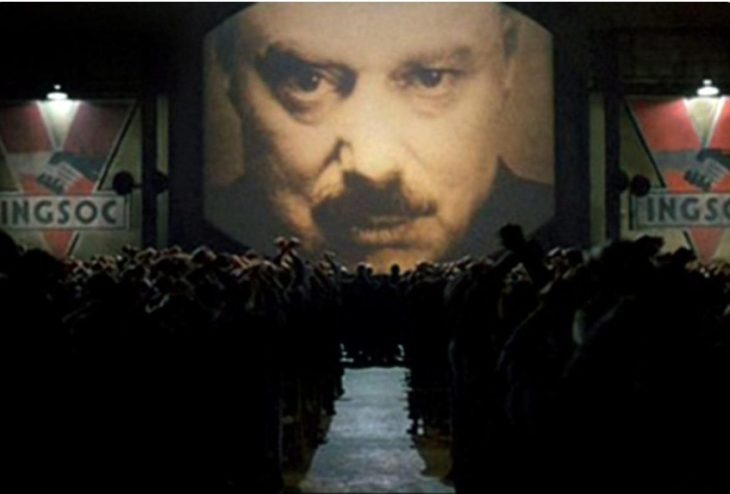

Today’s image is “Big Brother, the all-seeing dictator in 1984, as seen in the film version of the novel released in 1984 starring John Hurt as Winston Smith – Collection Christophel/Alamy Stock Photo” (https://www.yahoo.com/news/orwell-1984-now-comes-trigger-153837647.html). The article the photo is attached to concerns the publication of the 75th anniversary edition of the book with a new forward, one that provides a “trigger warning” to potential readers because of Orwell’s, or at least Winston’s, ungood attitude towards women.