Word of the Day: Necromancer

Today’s word of the day, continuing with our theme, is necromancer. Pronounced / ˈnɛk rəˌmæn sər /, with primary stress on the first syllable and secondary stress on the third syllable, this noun means “a person who uses witchcraft or sorcery, especially to reanimate dead people or to foretell the future by communicating with them” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/necromancer). Merriam-Webster defines it as “one that practices necromancy” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/necromancer). So we have another one of those definitions that depends upon another word we don’t know.

M-W defines necromancy as “conjuration of the spirits of the dead for purposes of magically revealing the future or influencing the course of events” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/necromancy). M-W says that the word first appears as the “Middle English nycromancie ‘sorcery, conjuration of spirits,’ borrowed from Late Latin necromantīa ‘divination from an exhumed corpse,’ borrowed from Late Greek nekromanteía ‘divination by conjuration of the dead,’ from Greek nekro- necro- + -manteia -mancy; replacing earlier Middle English nigromance, nygromancye, borrowed from Anglo-French nigromance, nigromancie, borrowed from Medieval Latin nigromantia, alteration of necromantia by association with Latin nigr-, niger ‘black’” (ibid.).

Etymonline.com says that necromancer first appears in the “late 14c., nygromanser, nigromauncere, sorcerer, adept in black magic,’ from Old French nigromansere, from nigromancie (see necromancy). Properly ‘one who communicates with the dead’ but typically used in a broader sense in English” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=necromancer). For necromancy, Etymonline says that it appears “c. 1300, nygromauncy, nigromauncie, ‘sorcery, witchcraft, black magic,’ properly ‘divination by communication with the dead,’ from Old French nigromancie ‘magic, necromancy, witchcraft, sorcery,’ from Medieval Latin nigromantia (13c.), from Latin necromantia ‘divination from an exhumed corpse,’ from Greek nekromanteia, from nekros ‘dead body’ (from PIE root *nek- ‘death’) + manteia ‘divination, oracle,’ from manteuesthai ‘to prophesy,’ from mantis ‘one who divines, a seer, prophet; one touched by divine madness,’ from mainesthai ‘be inspired,’ which is related to menos ‘passion, spirit’ (see mania). The spelling was influenced in Medieval Latin by niger ‘black,’ perhaps on notion of ‘black arts’ although in Latin the word also was used to signify death and misfortune. The modern English spelling is a mid-16c. correction” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/necromancy).

The spelling of the word is especially interesting. Coming from Latin necro-, meaning dead body, it is respelled with a g instead of a c (or k) because people associate it with “black magic,” and then notice that it ought to be spelled with a g because nigr in Latin is “black.” But in the 16th century, when scholars in England are working mostly in Latin, these scholars respelled the word. Some of the respellings done in the early modern English period were kind of dumb, like putting a b into doubt (the word borrowed from French was spelled douten), but I like this respelling.

On this date in 1688, “Quakers consider drafting formal protest of slavery in Germantown, Pennsylvania” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/february/18). Actually, they did more than consider it; they did it.

The Germantown Quaker Petition “was drafted by Francis Daniel Pastorius, a young German attorney and three other Quakers living in Germantown, Pennsylvania (now part of Philadelphia) on behalf of the Germantown Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends to raise the issue of slavery with the Quaker Meeting which they attended” (https://www.nps.gov/articles/quakerpetition.htm). They based their argument against slavery upon the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

The petition was presented at their local meeting and passed up the line to higher levels of organization. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting agreed to send the petition on to the London Meeting, but there is no record of whether it was sent to London or not. The meetings of the next London Meeting have no record of the petition’s being considered.

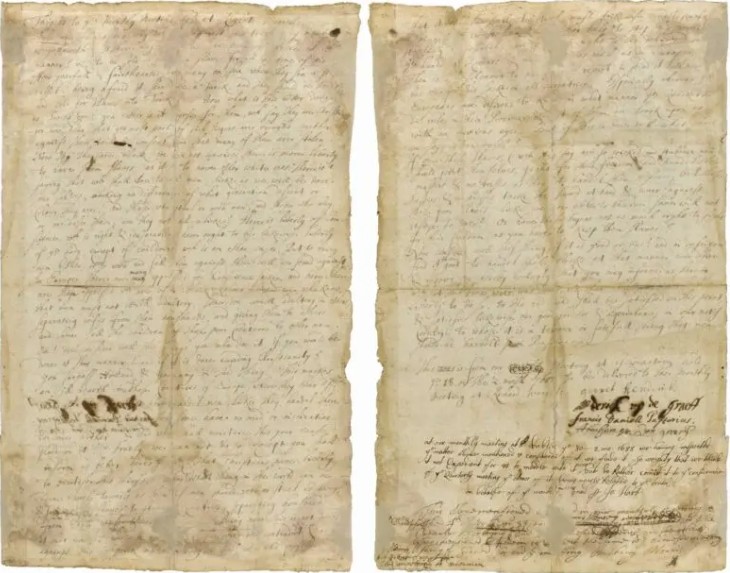

“The 1688 petition was set aside and forgotten until 1844 when it was re-discovered and became a focus of the burgeoning abolitionist movement. After a century of public exposure, it was misplaced and once more re-discovered in March 2005 in the vault at Arch Street Meetinghouse. It was discovered in deteriorating condition, with tears at the edges, paper tape covering voids and handwriting where the petition had originally been folded, and its oak gall ink slowly fading into gray. To preserve the document for future generations, it was treated at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts in downtown Philadelphia. It currently resides at Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, the joint repository (with Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College) for the records of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. Today the 1688 petition is for many a powerful reminder about the basis for freedom and equality for all” (ibid.).

Here’s the text of the Germantown Petition:

These are the reasons why we are against the traffick of men-body, as followeth. Is there any that would be done or handled at this manner? Viz., to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life? . . . There is a saying, that we shall doe to all men like as we will be done ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent or colour they are. And those who steal or robb men, and those who buy or purchase them, are they not all alike? Here is liberty of conscience, which is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of the body, except of evil-doers, which is another case. But to bring men hither, or to rob and sell them against their will, we stand against. In Europe there are many oppressed for conscience sake; and here there are those oppressed which are of a black colour. And we who know that men must not commit adultery,—some do commit adultery, in others, separating wives from their husbands and giving them to others; and some sell the children of these poor creatures to other men. Ah! Doe consider well this thing, you who doe it, if you would be done at this manner? And if it is done according to Christianity? You surpass Holland and Germany in this thing. This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe, where they hear off, that Quakers doe here handle men as they handle their cattle. And for that reason some have no mind or inclination to come hither. . . . Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating housbands from their wives and children. Being now this is not done in the manner we would be done at therefore we contradict and are against this traffic of men-body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid to purchase such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing if possible. And such men ought to be delivered out of the hands of the robbers, and set free as well as in Europe. Then is Pennsylvania to have a good report, instead it hath now a bad one for this sake in other countries. Especially whereas the Europeans are desirous to know in what manner the Quakers doe rule in their province;—and most of them doe look upon us with an envious eye. But if this is done well, what shall we say is done evil? . . .

This is from our meeting at Germantown, held the 18 of the 2 month, 1688, to be delivered to the Monthly Meeting at Richard Worrel’s. . . (https://billofrightsinstitute.org/activities/germantown-friends-antislavery-petition-1688/).

Brief personal connection. Germantown, founded by Quakers, was a separate town in the 17th and 18th centuries, absorbed into Philadelphia in 1854 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germantown%2C_Philadelphia). My mother grew up in Germantown. I don’t know if she knew about the history of Germantown or not. I got none of the information in this blog post from my mom; I couldn’t have since I’m not a necromancer.

Today’s image is of the Germantown Petition as it appears today in the library of Haverford College (https://billofrightsinstitute.org/activities/germantown-friends-antislavery-petition-1688/).