Word of the Day: Rodomontade

Today’s word of the day, thanks to the Word Guru daily email, is rodomontade, although the email uses the less common spelling, rhodomontade. Pronounced / ˌrɒd ə mɒnˈteɪd / or / ˌrou də mɒnˈteɪd / or maybe / ˌrɒd ə mɒnˈtɑd /, this noun means “vainglorious boasting or bragging; pretentious, blustering talk” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/rodomontade?misspelling=rodomonte&noredirect=true). Merriam-Webster explains, “Rodomontade (which can also be spelled rhodomontade) originated in Italian poetry. Rodomonte was a fierce and boastful king in Orlando Innamorato, Count Matteo M. Boiardo’s late 15th century epic, and later in the 1516 sequel Orlando Furioso, written by poet Lodovico Ariosto. In the late 16th century, English speakers began to use rodomont as a noun meaning ‘braggart.’ Soon afterwards, rodomontade entered the language as a noun meaning ‘empty bluster’ or ‘bragging speech,’ and later as an adjective meaning ‘boastful’ or ‘ranting’” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/rodomontade).

The word appears in English in the “1610s (earlier rodomontado, 1590s), ‘vain boasting like that of Rodomonte,’ a character in Ariosto’s Orlando furioso (earlier in Boiardo’s Orlando innamorato, Century Dictionary describes him as ‘a brave but somewhat boastful leader of the Saracens against Charlemagne.’ In dialectal Italian the name means literally ‘one who rolls (away) the mountain.’ As a verb, ‘boast, brag, talk big,’ by 1680s. Related: Rodomont ‘braggart’ (1590s)” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/rodomontade).

So from the various sources of daily words that I look at, I chose this word today because I have never heard of it before. I have never read Orlando furioso, not in translation nor in the original Italian. I have heard of it because it sometimes gets mentioned in, particularly, English Renaissance literature courses, especially ones that look at Spencer’s The Fairie Queene.

“Rodomonte first appears in Book 2, Canto i of Orlando innamorato. Boiardo was said to be so pleased at the invention of his name that he had the church bells rung in celebration. Boiardo, in Book 2, Canto xiv, says Rodomonte is the son of Ulieno, and a descendant of the Biblical giant Nimrod, from whom he inherited his massive sword, which was too heavy for an ordinary man to lift” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rodomonte). Rodomonte “is the King of Sarza and Algiers and the leader of the Saracen army which besieges Charlemagne in Paris. He is in love with Doralice, Princess of Granada, but she elopes with his rival Mandricardo. He tries to seduce Isabella but she tricks him into killing her by mistake. In remorse, Rodomonte builds a bridge in her memory and forces all who cross it to pay tribute. When the ‘naked and mad’ Orlando arrives at the bridge, it is Rodomonte, the pagan, who throws him into the river below. They both swim ashore, but Orlando who is naked and is unimpeded by heavy armor gets to the shore first. Finally, Rodomonte appears at the wedding of Bradamante and Ruggiero and accuses Ruggiero of treason for converting to Christianity and abandoning the Saracen cause. The two fight a duel and Rodomonte is killed” (ibid.).

Boiardo’s Orlando innamorato (Orlando [or Roland] in love) is an epic poem concerning the same characters we find in the Le Chanson de Roland (The Song of Roland), the 11th or early 12th romance/epic focusing on the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, at which part of Charlemagne’s army, led by Roland, was cut off by a Basque army and wiped out. The Song of Roland is considered the oldest work in French literature. Ariosto’s Orlando furioso (The Frenzy of Orlando) picks up where Boiardo’s work ended; Boiardo said that he stopped writing in 1486 because Italy had been at war.

Critics consider Rodomonte as the third protagonist of the Orlando epics, although early criticism and more recent criticism differ as to whether he is heroic or not. But in English the earliest understanding of Rodomonte is that he was a braggart, and thus we have the word.

Words derived from the names of characters like Rodomonte are not rare in English. Here are a few examples:

Quixotic: an adjective derived from the name of Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. A quixotic person is someone who is foolish, particularly in pursuit of ideals.

Malapropism: a noun taken from the name of a character, Mrs. Malaprop, in Richard Sheridan’s 18th century play The Rivals. A malapropism is an abuse of the language that occurs when someone tries to use a big word but gets is slightly wrong, a behavior that Mrs. Malaprop was frequently guilty of, to comic effect.

Pooh-bah: a noun taken from the name of a character in Gilbert and Sullivan’s 1885 operetta The Mikado; it now means “a person who holds several positions, especially ones that give bureaucratic importance” or “a pompous, self-important person.”

Pander: a noun taken from the name of a character, Pandarus, in Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde; a pander is someone who acts as a kind of pimp, someone who procures a woman for someone else.

Gargantuan: an adjective taken from the name of a character, Gargantua, in Rabelais’s satire of the same name; Gargantua is a giant with a gigantic appetite, and thus the adjective refers to anything that is very large.

Perhaps the most interesting one of all is a noun that is derived from a sixteenth-century poem by Girolamo Fracastoro, a poet, scholar and physician. Fracastoro came up with the idea of seeds of contagion, a precursor to the germ theory of illness. One of his works concerns a shepherd who catches a sexually transmitted disease; the poem is called Syphilis sive morbus gallicus (“Syphilis or The French Disease”) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girolamo_Fracastoro).

I’m actually proud of the fact that I have never had to deal with mercury as a cure, as Fracastoro suggests in the poem, though my pride won’t cause me to engage in a rodomontade.

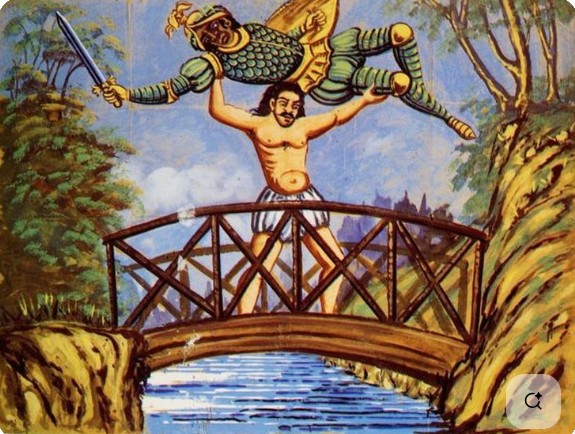

Today’s image, found on Pinterest of all places, shows Roland (Orlando) throwing Rodomonte off a bridge.