Word of the Day: Irascible

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of the Word Guru daily email, is irascible. According to Dictionary.com, it is pronounced / ɪˈræs ə bəl / (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/irascible), but I think I disagree. I know that the rule in English is that vowels in unstressed syllables tend toward schwa, but in this case I think most people will pronounce that third syllable with ɪ, what we used to call a short i. The consonant sound that precedes the vowel is / s /, and the consonant that follows it is / b /, and both of those consonants are formed in the front of the mouth. S is “a voiceless alveolar sibilant (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S), so it is produced with the tongue up against the alveolar ridge, near the front of the mouth. B is “the voiced bilabial stop” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B), so it is produced with the two lips, also at the front of the mouth. The ɪ is a “near-close near-front unrounded vowel” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Near-close_near-front_unrounded_vowel), whereas the schwa “is articulated with the tongue in a generally central position within the mouth” (https://www.britannica.com/topic/schwa). So while normally it takes less effort to pronounce a schwa instead of another vowel sound, in this case it would actually be more work for the speaker to go from a front consonant to a middle vowel and back to a front consonant. I’m guessing that most people would use the unstressed ɪ. It’s another example of the Principle of Least Effort.

The adjective means “easily provoked to anger; very irritable” or “characterized or produced by anger” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/irascible). Merriam-Webster says, “If you try to take apart irascible on the model of irrational, irresistible, and irresponsible you might find yourself wondering what ascible means—but that’s not how irascible came to be. The key to the meaning of irascible isn’t the negating prefix ir- (which is the form of the prefix in- that is used before words beginning with ‘r’), but rather the Latin noun ira, meaning ‘anger.’ From ira, which is also the root of irate and ire, came the Latin verb irasci (“to become angry”) and the related adjective irascibilis, the latter of which led to the French word irascible. English speakers borrowed the word from French in the 16th century” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/irascible).

But Etymonline.com says that it entered the English language “late 14c., from Old French irascible (12c.) and directly from Late Latin irascibilis, from Latin irasci ‘be angry, be in a rage,’ from ira ‘anger’ (see ire)” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/irascible). The root word, ire, entered the language “c. 1300, from Old French ire ‘anger, wrath, violence’ (11c.), from Latin ira ‘anger, wrath, rage, passion,’ from PIE root *eis- (1), forming various words denoting passion (source also of Greek hieros ‘filled with the divine, holy,’ oistros ‘gadfly,’ originally ‘thing causing madness;’ Sanskrit esati ‘drives on,’ yasati ‘boils;’ Avestan aesma ‘anger;’ Lithuanian aistra ‘violent passion’). Old English irre in a similar sense is unrelated; it is from an adjective irre ‘wandering, straying, angry,’ which is cognate with Old Saxon irri ‘angry,’ Old High German irri ‘wandering, deranged,’ also ‘angry;’ Gothic airzeis ‘astray,’ and Latin errare ‘wander, go astray, angry’ (see err (v.))” (ibid.).

According to On This Day, on this date in 1865 “P. T. Barnum’s museum in New York burns down, giantess Anna Haining Swan just escapes” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/july/13).

Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810-1891) was an American entrepreneur and showman, “The Greatest Showman” if one is to believe the title of the movie made about him and starring Hugh Jackman (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P._T._Barnum). In 1841, Barnum purchased Scudder’s American Theater in New York City, a five-story building on the corner of Broadway and Ann Street; it was across the street from the St. Paul Chapel, “the oldest surviving church building in Manhattan and one of the nation’s most well renowned examples of Late Georgian church architecture” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Paul%27s_Chapel). Barnum bought the theater when the original purchaser failed to make a payment and Barnum was able to step in (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barnum%27s_American_Museum).

Barnum’s “museum” was really a showcase for all sorts of entertainment, sort of a combination museum, carnival side show, theater, and lecture hall. It had a negative reputation among some people, in part because it contained exhibits that were downright hoaxes, like the skeleton of a mermaid or the trunk of a tree that Jesus’s apostles sat under, as well as oddities, like a bearded woman and General Thom Thumb. But it was also an educational institution of sorts, containing exhibits with animals like beluga whales, scientific instruments, and craft workers. “At its peak, the museum was open fifteen hours a day and had as many as 15,000 visitors a day.[1] Some 38 million customers paid the 25 cents admission to visit the museum between 1841 and 1865. The total population of the United States in 1860 was under 32 million” (ibid.).

But despite the popularity, not everyone was happy to have the Barnum circus in town. “In November 1864, the Confederate Army of Manhattan attempted and failed to burn down the museum, but on July 13, 1865, the American Museum burned to the ground in one of the most spectacular fires New York has ever seen. Animals at the museum were seen jumping from the burning building, only to be shot by police. Many of the animals unable to escape the blaze burned to death in their enclosures, including the two beluga whales who burned to death after the glass panes of their tank were broken in an attempt to quell the fire. It was allegedly during this fire that a fireman by the name of Johnny Denham killed an escaped tiger with his ax before rushing into the burning building and carrying out a 400-pound woman on his shoulders” (ibid.). Barnum opened a new museum at another location, but it, too, burned down just three years later.

Barnum also used the museum to push his temperance attitude, which was popular among a lot of women. Barnum very much opposed alcohol (ibid.).

Barnum was an interesting mix, then, of moralist and businessman. One instance of the latter appears in this little story: “Barnum noticed that people were lingering too long at his exhibits. He posted signs indicating ‘This Way to the Egress’. Not knowing that ‘Egress’ was another word for ‘Exit’, people followed the signs to what they assumed was a fascinating exhibit — and ended up outside” (ibid.).

Barnum also got involved in politics, initially as a Democrat, but later as a Republican. He left the Democrats over the issue of slavery. “He acknowledged that he had owned slaves when he lived in the South: ‘I whipped my slaves. I ought to have been whipped a thousand times for this myself. But then I was a Democrat—one of those nondescript Democrats, who are Northern men with Southern principle’” (ibid.). As a member of the Connecticut legislature, he sponsored “an 1879 law that prohibited the use of ‘any drug, medicinal article or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception’ and criminalized acting as an accessory to the use of contraception. This law remained in effect in Connecticut until it was overturned in 1965 by the U.S. Supreme Court in its Griswold v. Connecticut decision” (ibid.).

And despite his reputation for pulling off hoaxes in his museum, he actually worked to expose the kinds of frauds who preyed upon people: “he exposed the tricks employed by mediums to cheat the bereaved. In The Humbugs of the World, Barnum offered $500 (equivalent to $10,271 in 2024) to any medium who could prove the power to communicate with the dead” (ibid.).

So P. T. Barnum, in addition to his circus, was well-known as a philanthropist, a politician, and a moralist. But I found no evidence that he was irascible. There is also no evidence that he ever said, “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

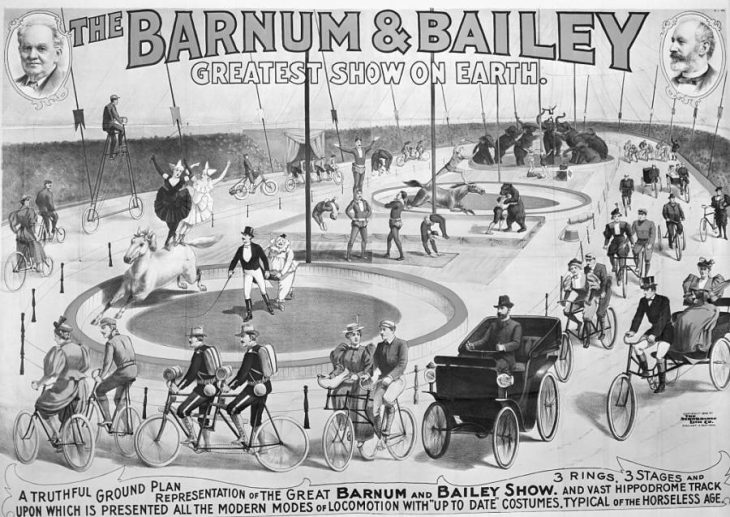

Today’s image is of a poster for the Barnum and Bailey Circus (https://allthatsinteresting.com/pt-barnum-facts?utm_source=Pinterest&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=twitter_snap). If you have seen the movie “The Greatest Showman,” you may be surprised that Barnum didn’t get into the circus business until he was 60, which is why the image of him in the upper lefthand corner is of an older man, and one who looks nothing like Hugh Jackman.