Word of the Day: Whilom

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary), is whilom. Whilom is an adverb that means “former; erstwhile” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/whilom). In his 1755 Dictionary, Samuel Johnson defines it as “Formerly; once; of old,” but in the 1773 update of the Dictionary, he adds, “Not in use” because the word had become obsolete (https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/views/search.php?term=whilom).

Etymonline.com says that it appears in the language “c. 1200, from Old English hwilum ‘at times,’ dative of while (q.v.). As a conjunction from 1610s. Similar formation in German Weiland ‘formerly’” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/whilom). The website then expands upon the nominative form, while: “’span of time,’ especially ‘short space of time during which something is to happen or be done or certain conditions prevail;’ Old English hwile, accusative of hwil ‘a space of time,’ from Proto-Germanic *hwilo, which is reconstructed to be from PIE *kwi-lo-, suffixed form of root *kweie- ‘to rest, be quiet.’ The notion of ‘period of rest’ became in Germanic ‘period of time.’ Now largely superseded by time (n.) but preserved in formulaic constructions (such as all the while). The sense of ‘time spent in doing something, expenditure of time’ is in worthwhile and phrases such as worth (one’s) while. As a conjunction, ‘at the same time that; as long as’ (late Old English), it represents Old English þa hwile þe, literally ‘the while that’” (ibid.).

Merriam-Webster elaborates: “Whilom shares an ancestor with the word while. Both trace back to the Old English word hwīl, meaning ‘time’ or ‘while.’ In Old English hwīlum was an adverb meaning ‘at times.’ This use passed into Middle English (with a variety of spellings, one of which was whilom), and in the 12th century the word acquired the meaning ‘formerly.’ The adverb’s usage dwindled toward the end of the 19th century, and it has since been labeled archaic. The adjective first appeared on the scene in the 15th century, with the now-obsolete meaning ‘deceased,’ and by the 19th century it was being used with the meaning ‘former.’ It’s a relatively uncommon word, but it does see occasional use” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/whilom). It seems a bit confusing that M-W says that its use dwindled in the 19th century even though Johnson, in the 18th century, said that it was “not in use.” Language often changes slowly.

It’s pronounced / ˈʰwaɪ ləm / or/ ˈwaɪ ləm /, according to Dictionary.com (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/whilom). When I was in grammar school, our teachers insisted that we begin certain words with the aspiration represented by that little superscript h that you see in the first pronunciation: words like why (/ ʰwaɪ /, what (/ ʰwʌt /), and whether (/ ˈʰwɛð ər /. That pronunciation goes back to the Old English. For instance, the first word in the Old English epic Beowulf is Hwæt, which will become the word what in contemporary English. Why is hwi in OE and whether is hwæðer. Not to disparage my grammar school teachers, but I doubt that they knew the Old English and that in OE the w and the h were reversed, and as I remember they never insisted that we pronounce who as / ʰwu / even though the OE is hwa. But at least in contemporary American English, that aspiration has disappeared entirely except from the most pedantic of speakers. I don’t know about other contemporary Englishes, but I expect it has disappeared from those dialects as well, based upon the Principle of Least Effort. If you know differently, please share.

According to On This Day, on this date in 1613, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London burns down during a performance of ‘Henry VIII’” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/june/29).

The story of the building of the The Globe in 1599 is a fun story. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men (the company of which Shakespeare was a shareholder as well as an actor and the chief playwright) had a building called The Theater, but it was on rented land. At the end of the lease in 1598, the owner, Giles Allen, decided not to renew, meaning that the company might lose their venue. They bought some land in Southwark, and on December 28, 1598, while Allen was at his country home celebrating the holidays, in the middle of the night, the company disassembled The Theater and transported it across the Thames to its new site. The Globe was not an exact replica of The Theater; in fact, it was larger. And it had to be built on a kind of wharf because the land was prone to flooding. It probably took much of the year to complete the building, and it probably opened in September, although some historians argue that it may have opened as early as June (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Globe_Theatre).

Toward the end of his career as a playwright, Shakespeare collaborated with John Fletcher, who would later succeed Shakespeare as the King’s Men’s primary playwright (the company was given the patronage of James I upon his accession to the throne) on a play about certain parts of the reign of King Henry VIII. Its original title was All Is True. In the last act, which featured the birth to Ann Boleyn of a daughter, Elizabeth, who will later become Queen Elizabeth I, there was a masque, and as part of the masque there was a special effect, a cannon blast. We don’t know when the play was first performed, but the first recorded performance was that on the 29th of June, 1613 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_VIII_(play)).

The cannon on that day was filled with wadding, basically paper, not a cannon ball, and was pointed up. Unfortunately, a small piece of that paper, set alight by the blast, got caught up in the roof. The roofs of most Elizabethan London buildings was thatch, which was basically straw woven together to make a waterproof mat. But while waterproof, thatch was not fireproof. Thatch had been outlawed in London proper hundreds of years earlier, but Southwark was not in London. And after the Great Fire of 1666, the ban on thatch roofs was enforced even more strictly. And on that day in 1613, the thatch roof caught fire.

Sir Henry Wotton, who was a spectator, wrote, “Now, to let matters of state sleep, I will entertain you at the present with what happened this week at the Bankside. The King’s players had a new play, called All is True, representing some principal pieces of the reign of Henry VIII, which was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and majesty, even to the matting of the stage; the Knights of the Order with their Georges and garters, the Guards with their embroidered coats, and the like: sufficient in truth within a while to make greatness very familiar, if not ridiculous. Now, King Henry making a masque at the Cardinal Wolsey’s house, and certain chambers being shot off at his entry, some of the paper, or other stuff, wherewith one of them was stopped, did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but an idle smoke, and their eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly, and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the whole house to the very grounds” (https://www.shakespeare-online.com/faq/henryVIIIfaq.html).

The Globe was rebuilt and stayed upon until Parliament, run by the Puritans, closed all the theaters in 1642. In 1997, a new “Shakespeare’s Globe” was built on almost the same site, though this new building is full enclosed and has modern amenities. In the meanwhile, Shakespeare’s plays were performed in many other places, indoors, such as the Blackfriars in Elizabethan London, and out, such as the Shakespeare in the Park in Greenville, SC, where it is actually save though unnecessary to fire off a cannon for a sound effect.

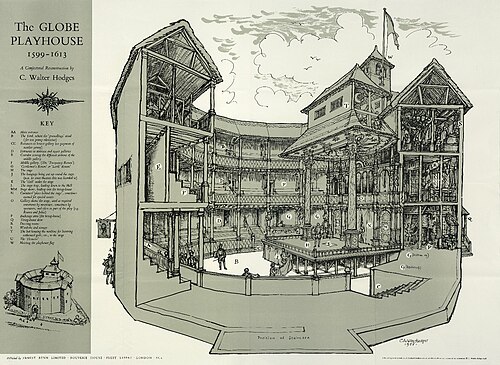

The image today is a “Conjectural reconstruction of the Globe theatre by C. Walter Hodges based on archaeological and documentary evidence” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Globe_Theatre).