Word of the Day: Holus-bolus

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary), is holus-bolus. A hyphenated compound word, holus-bolus, pronounced / ˈhoʊ ləsˈboʊ ləs /, is an adverb that means “all at once; altogether” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/holus-bolus). Dictionary.com goes on to explain that it was “First recorded in 1840–50; mock-Latin rhyming compound based on the phrase whole bolus, or possibly a Latinization of Greek hólos bôlos ‘whole lump, clod of earth, nugget’” (ibid.). A bolus is either “a round mass of medicinal material, larger than an ordinary pill” or “a soft, roundish mass or lump, especially of chewed food” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/bolus).

Merriam-Webster goes further: “The story of holus-bolus is not a hard one to swallow. Holus-bolus originated in English dialect in the mid-19th century and is believed to be a waggish reduplication of the word bolus. Bolus is from the Greek word bōlos, meaning ‘lump,’ and has retained that Greek meaning. In English, bolus has additionally come to mean ‘a large pill,’ ‘a mass of chewed food,’ or ‘a dose of a drug given intravenously.’ Considering this ‘lumpish’ history, it’s not hard to see how holus-bolus, a word meaning ‘all at once’ or ‘all in a lump,’ came about” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/holus-bolus).

Given that it didn’t appear in English until 1840-50, we shouldn’t be surprised that it is not in Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary. But it is a bit surprising that Etymonline.com not only lacks an entry for holus-bolus but also has no entry for bolus.

By the way, reduplication in linguistics “is a morphological process in which the root or stem of a word, part of that, or the whole word is repeated exactly or with a slight change” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reduplication). There are lots of different types of reduplication in languages around the world, and there are many different reasons for such reduplication—morphological, semantic, grammatical. The uses of reduplication in English are less, and the types of reduplication are somewhat limited. They include rhyming (itsy-bitsy, teenie-weenie), exact (papa, poo-poo, yoyo), ablaut, where the first vowel is a high or front vowel and the second a low or back vowel (hip hop, zig zag), and a special American class in English that derived from Yiddish called shm reduplication (fancy-shmancy), among others (ibid.).

Reduplication is also familiar to the parents of toddlers. “At 25–50 weeks after birth, typically developing infants go through a stage of reduplicated or canonical babbling (Stark 198, Oller, 1980). Canonical babbling is characterized by repetition of identical or nearly identical consonant-vowel combinations, such as nanana or idididi. It appears as a progression of language development as infants experiment with their vocal apparatus and home in on the sounds used in their native language. Canonical/reduplicated babbling also appears at a time when general rhythmic behavior, such as rhythmic hand movements and rhythmic kicking, appear. Canonical babbling is distinguished from earlier syllabic and vocal play, which has less structure (ibid.). I didn’t become interested in linguistics and language development until well after my own children were grown, but I have enjoyed noticing the development of language in my grandchildren, and it was fun to listen to this canonical babbling when they were very small.

On this date in 1770, Anthony Benezet opened a school in Philadelphia, PA.

Anthony Benezet (1713-1784) was born in France to parents who were French Huguenots, a group of Protestants who were actively persecuted by the French church and state. Eventually, his family moved out of France In 1731, they finally settled in Philadelphia. When he was in London, he joined the Society of Friends, also known as Quakers (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Benezet).

In 1739, Benezet began teaching at a school in Germantown, which was then outside of Philadelphia but is now part of the city (my mother grew up in Germantown). “In 1742, he moved to the Friends’ English School of Philadelphia (now the William Penn Charter School). In 1750 he added night classes for black slaves to his schedule. In 1755, Benezet left the Friends’ English School to set up his own school, the first public girls’ school on the American continent. His students included daughters from prominent families” (ibid.).

Then in 1770 Benezet opened a school for African-Americans. The community of African-Americans in Philadelphia had been growing, especially after the state banned the importation of slaves in 1767. Benezet, like all the Quakers, was an abolitionist, and he was quite influential. He had been teaching African-American children and adults in night school for some years in his home. “In 1773, Jacob Lehre, a schoolteacher working for Benezet, took over the education of approximately 50 Black children. By 1775, only nine remained. The school’s Board of Overseers decided to visit all the parents to encourage better attendance. They also set out a call to admit poor white children to fill up the classroom. Lehre began teaching both 40 Black and six white students–boys and girls–in his classroom, perhaps the first integrated (and co-ed) urban school in America (though a charity school, not a public one)” (https://katebahlkehornstein.com/2022/08/18/anthony-benezets-revolutionary-academy-for-children/).

In 1775, Benezet “helped found the first anti-slavery society, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. Eight years later in 1783, Benezet wrote a letter to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz discussing ‘the cruelty of slavery and his opposition to the slave trade.’ After Benezet’s death, Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Benjamin Rush reconstituted this association as the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Benezet).

Anthony Benezet is not a familiar name, not a name that one comes across often in one’s study of American history. But he was, apparently, a person who lived out his faith and his values, and encouraged others to do the same. And one of the things he believed in was that the holus-bolus of society needs and deserves an education.

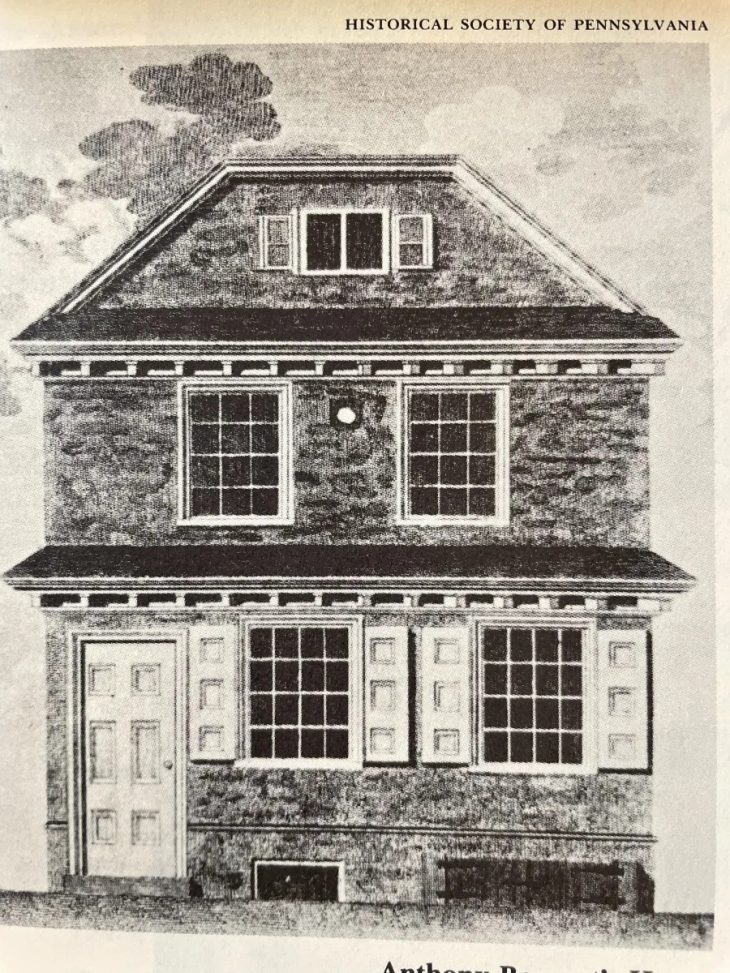

Today’s image is of Benezet’s home: “Benezet set up a school for free Black children in his home on Chestnut Street between 3rd and 4th Streets” (https://katebahlkehornstein.com/2022/08/18/anthony-benezets-revolutionary-academy-for-children/).