Word of the Day: Querimony

Today’s word of the day, thanks to the Word Guru daily email, is querimony. According to the email, querimony, pronounced either [kwer-uh-moh-nee] (according to the email, which would translate in IPA as / ˈkwɛr ɪ ˌmou ni /) or / ˈkwɛrɪmənɪ / (https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/querimony), is a noun that means “complaint or lamentation; the act of complaining,” according to the email. Collins Dictionary says that it is obsolete.

That sense that it is an obsolete word is reinforced by the fact that when I looked it up at Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster I got no responses. I also got no response when I looked it up on the website that features Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary. When I looked up querimony on Etymonline.com, I did not get anything for it, but I did get the following for querimonius: “’complaining, apt to complain,’ c. 1600, from Latin querimonia ‘a complaint,’ from queri ‘to complain’ (see querulous)” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/querimonious).

Then it says this about querulous: “’habitually complaining; expressing complaint,’ c. 1400, querelous, from Old French querelos ‘quarrelsome, argumentative’ and directly from Late Latin querulosus, from Latin querulous ‘full of complaints, complaining,’ from queri ‘to complain,’ from Proto-Italic *kwese-, of uncertain etymology, perhaps, via the notion of ‘to sigh,’ from a PIE root *kues- ‘to hiss’ (source also of Sanskrit svasiti ‘to hiss, snort’), which is not very compelling, but no better etymology has been offered” (ibid.).

So what we have today is an obsolete word that is of uncertain origin. But the Word Guru email justifies its inclusion among its Word of the Day emails this way: “Querimony comes from the Latin querimonia, meaning ‘complaint’ or ‘lament.’ While rarely used in modern English, it once appeared in legal and poetic contexts to express formal grievances or sorrowful complaints. Unlike casual grumbling, querimony suggests an eloquent, almost artistic, expression of discontent. Its use evokes a more classical or stylized form of complaining—more monologue than moan. Reviving this word today adds a touch of flair to any description of well-worded dissatisfaction.”

According to the On This Day website, on this date in 1377, “10-year-old Richard of Bordeaux succeeds his grandfather Edward III as Richard II, King of England” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/june/22).

Edward III (1312-1377) succeeded his father, Edward II, when he was just 14 years old. His father had been deposed and murdered by his wife Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer. Christopher Marlowe’s The Troublesome Reign and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second, King of England, with the Tragical Fall of Proud Mortimer concerns those events. But despite the early age at which he took the throne, Edward III had, by king standards, a long and successful reign. Edward had eight sons, but the oldest, and the heir to the throne, Edward of Woodstock or Edward the Black Prince, died the year before his father. Because of the practice of primogeniture, the Black Prince’s eldest son, Richard, inherited the bulk of his grandfather’s estate, including the crown of England.

Like his grandfather, Richard II inherited the kingdom at an early age, but unlike Edward, Richard’s reign was not exactly successful, not even by the standards of medieval kings. He had some success with the Peasants Revolt in 1381, but he didn’t like the controls put upon him by his uncles, who served as regents during Richard’s youth. In fact, Richard’s reign was much more like that of his great grandfather, Edward II. And in 1399, he, too, was deposed, this time by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke, who became Henry IV.

William Shakespeare’s The Life and Death of King Richard the Second covers the end of Richard’s reign and life. Whenever I taught Shakespeare, I began the semester with Richard II because it’s a play a really love, though I have to admit that very few of my students were as intrigued by it as I am. My students never seemed to like Richard, and it is true that Richard, early in the play, is not exactly likeable. However, Richard becomes, later in the play, the master of suffering (or maybe it’s the master of self-pity). I’m going to provide a couple of examples.

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings;

How some have been deposed; some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed;

Some poison’d by their wives: some sleeping kill’d;

All murder’d: for within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps Death his court and there the antic sits,

Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp,

Allowing him a breath, a little scene,

To monarchize, be fear’d and kill with looks,

Infusing him with self and vain conceit,

As if this flesh which walls about our life,

Were brass impregnable, and humor’d thus

Comes at the last and with a little pin

Bores through his castle wall, and farewell king!

Cover your heads and mock not flesh and blood

With solemn reverence: throw away respect,

Tradition, form and ceremonious duty,

For you have but mistook me all this while:

I live with bread like you, feel want,

Taste grief, need friends: subjected thus,

How can you say to me, I am a king? (Richard II 3.2)

What must the king do now? must he submit?

The king shall do it: must he be deposed?

The king shall be contented: must he lose

The name of king? o’ God’s name, let it go:

I’ll give my jewels for a set of beads,

My gorgeous palace for a hermitage,

My gay apparel for an almsman’s gown,

My figured goblets for a dish of wood,

My sceptre for a palmer’s walking staff,

My subjects for a pair of carved saints

And my large kingdom for a little grave,

A little little grave, an obscure grave;

Or I’ll be buried in the king’s highway,

Some way of common trade, where subjects’ feet

May hourly trample on their sovereign’s head;

For on my heart they tread now whilst I live;

And buried once, why not upon my head? (Richard II 3.3)

And there is the amazing, beautiful soliloquy in 5.5, which you can read here: https://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/views/plays/play_view.php?WorkID=richard2&Act=5&Scene=5&Scope=scene&displaytype=print.

And then there is the beautiful though ahistorical scene between Richard and his Queen, Anne. Anne had actually died in 1394, five years before the events in Shakespeare’s play, and in 1396 Richard had married Isabella of Valois, who was only 6. But according to Holinshed’s Chronicles, one of Shakespeare’s chief sources for his history plays, Richard and Anne loved each other and could hardly be separated. Shakespeare captures that love in Act 5, scene 1, which ends with Richard saying, “We make woe wanton with this fond delay: / Once more, adieu; the rest let sorrow say.”

Richard may have been good at matrimony, at least with his first wife, but Shakespeare’s version of Richard was also a master of querimony.

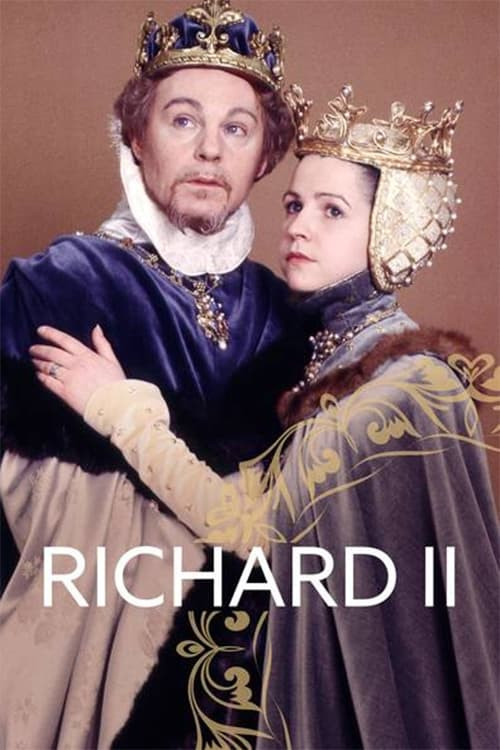

Today’s image is of Derek Jacobi and Janet Maw in the 1978 BBC production of Richard II (https://letterboxd.com/film/richard-ii-1978/). It’s worth watching.