Word of the Day: Esoteric

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Words Coach (https://www.wordscoach.com/dictionary) is esoteric. According to Dictionary.com, the pronunciation is / ˌɛs əˈtɛr ɪk /, which is somewhat surprising because, despite the rule about unstressed syllables tending toward schwa, I have never heard any say anything other than / ˌɛs oˈtɛr ɪk / (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/esoteric). It’s an adjective that means “understood by or meant for only the select few who have special knowledge or interest,” or “belonging to the select few,” or “private; secret; confidential,” or “(of a philosophical doctrine or the like) intended to be revealed only to the initiates of a group” (ibid.).

The word first appears in the language in the “1650s, from Latinized form of Greek esoterikos ‘belonging to an inner circle’ (Lucian), from esotero ‘more within,’ comparative adverb of eso ‘within,’ from PIE *ens-o-, suffixed form of ens, extended form of root *en ‘in.’ Classically applied to certain writings of Aristotle of a scientific, as opposed to a popular, character; later to doctrines of Pythagoras. In English, first of Pythagorean doctrines” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=esoteric).

Merriam-Webster discusses not only esoteric but its opposite: “The opposite of esoteric is exoteric, which means ‘suitable to be imparted to the public.’ According to one account, those who were deemed worthy to attend the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s learned discussions were known as his ‘esoterics,’ his confidants, while those who merely attended his popular evening lectures were called his ‘exoterics.’ Since material that is geared toward a target audience is often not as easily comprehensible to outside observers, esoteric acquired an extended meaning of ‘difficult to understand.’ Both esoteric and exoteric started appearing in English in the 17th century; esoteric traces back to ancient Greek by way of the Late Latin esotericus. The Greek esōterikos is based on the comparative form of esō, which means ‘within’” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/esoteric). But I don’t think I have ever heard exoteric used, whether in an academic setting or in everyday speech.

On this date in 1784, according to the On This Day website, “Holland forbids the wearing of orange clothes” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/june/16). From an historical perspective, this event is a bit crazy, but before I talk about it, I want to start with one of those questions of everyday philosophy, “Which came first, the color or the fruit?” According to Etymonline.com, it was clearly the fruit, at least in English. Orange appears in English in the “late 14c., in reference to the fruit of the orange tree (late 13c. as a surname), from Old French orange, orange (12c., Modern French orange), from Medieval Latin pomum de orenge, from Italian arancia, originally narancia (Venetian naranza), an alteration of Arabic naranj, from Persian narang, from Sanskrit naranga-s ‘orange tree,’ a word of uncertain origin” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=orange). Then it continues, “Not used as a color word in English until 1510s (orange color), ‘a reddish-yellow color like that of a ripe orange.’ Colors similar to modern orange in Middle English might be called citrine or saffron. Loss of initial n- probably is due to confusion with the definite article (as in une narange, una narancia), but also perhaps was by influence of French or ‘gold’” (ibid.).

The Principality of Orange was a state in the southern part of modern-day France until the early 18th century. In 1544, William of Nassau-Dillenburg inherited the state from his cousin, and he fashioned himself William of Nassau-Orange, though he would later be known as William the Silent (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Orange-Nassau). William also had a lot of property in the Netherlands. So even though France eventually took over the province of Orange, the prince of the Netherlands kept the title for a long time.

For many years, the color of orange, particularly when worn, was popular among the Dutch. The story was that the color was adopted by William I, who led a revolt against the Spanish and won independence for the Netherlands. Even after the loss of the principality of Orange, the governors of the Netherlands, called stadtholders, continued to wear orange.

In the latter part of the 18th century, the stadtholder was William V: he “was a controversial figure, and was seen by many as a weak and ineffective ruler. He was also deeply unpopular with the so-called “patriots,” a political movement that sought to reform the Dutch government and reduce the power of the stadtholders. Despite this, William V continued to be associated with the color orange, and was known to wear orange clothes and accessories” (https://travelasker.com/what-led-to-the-prohibition-of-wearing-orange-clothes-in-holland-in-the-year-1784/).

“The patriots were a diverse group of people who shared a common goal: the reform of the Dutch government and the reduction of the stadtholder’s power. The patriots were made up of merchants, intellectuals, and other members of the middle class, as well as some lower-class citizens. They were inspired by Enlightenment ideas and the American Revolution, and sought to create a more democratic and egalitarian society. The patriots were also critical of the stadtholder and the aristocracy, which they saw as corrupt and self-serving. As the patriots gained more support and visibility, tensions between them and the stadtholder increased” (ibid.).

For some reason, the patriots decided that there color was blue. They wore blue clothes and carried blue banners. So it got to be pretty easy to tell who was on which side. As tensions increased, so did the violence. “In 1784, the Dutch government issued an edict banning the wearing of orange clothes in Holland. The reasons for this decision are not entirely clear, but it is likely that the government was seeking to defuse tensions between the patriots and the stadtholder by removing the symbolic power of the color orange. The edict was met with outrage by many Dutch citizens, who saw it as an attack on their national identity and traditions” (ibid.).

Now, what seems really strange in this is that the Dutch government banned the color that was symbolic of the Dutch government, in a sense. One would think that the government would have banned the wearing or the carrying of blue, the side of the opposition. In the Middle Ages, many European countries forbade the populace from wearing certain colors, but this was so that the elites could have something that was only theirs, some esoteric.

The patriots eventually won, but not without help. The ban on orange was lifted with the creation of the Batavian Republic, which really was a client state of Napoleonic France (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batavian_Republic). But even then it seems odd that the patriots, who opposed the people who wore orange, would lift the ban on the wearing of orange. Maybe they wanted the supporters of William V to show themselves.

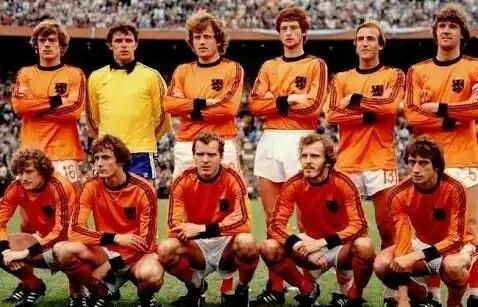

Today’s image is of the 1974 Dutch National team that lost to West Germany in the final of the World Cup (https://www.pinterest.com/pin/783133822675035378/). Not only does the team regularly wear orange, it is called Oranje, “their fan club is known as Het Oranje Legioen (The Orange Legion)” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netherlands_national_football_team). The Dutch have been World Cup runner up three times. This 1974 squad featured Johan Cruyff, one of the best and most innovative footballers to ever play the game.