Word of the Day: Chagrin

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Merriam-Webster, is chagrin. The word can be used as either a noun or a verb, but the pronunciation is the same in either case, although the pronunciation, specifically the stress, is different between American English and British English. As a noun, it means “disquietude or distress of mind caused by humiliation, disappointment, or failure” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/chagrin). As a verb, it means “to vex or unsettle by disappointing or humiliating” (ibid.).

M-W adds the following: “Despite what its second syllable may lead one to believe, chagrin has nothing to do with grinning or amusement—quite the opposite, in fact. Chagrin, which almost always appears in phrases such as ‘to his/her/their chagrin,’ refers to the distress one feels following a humiliation, disappointment, or failure. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the word’s French ancestor, the adjective chagrin, means ‘sad.’ What may be surprising is that the noun form of the French chagrin, meaning ‘sorrow’ or ‘grief,’ can also refer to a rough, untanned leather (and is itself a modification of the Turkish word sağrı, meaning ‘leather from the rump of a horse’). This chagrin gave English the word shagreen, which can refer to such leather, or to the rough skin of various sharks and rays” (ibid.)

But etymonline somewhat disagrees with M-W on the etymology of chagrin. That website says that the words appears in the English language in the “1650s, ‘melancholy,’ from French chagrin ‘melancholy, anxiety, vexation’ (14c.), from Old North French chagreiner or Angevin dialect chagraigner ‘sadden,’ which is of unknown origin, perhaps [Gamillscheg] from Old French graignier ‘grieve over, be angry,’ from graigne ‘sadness, resentment, grief, vexation,’ from graim ‘sorrowful,’ which is perhaps from a Germanic source (compare Old High German gram ‘angry, fierce’) (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=chagrin).

But then etymonline refers to another theory that comes from the Oxford English Dictionary: “But OED and other sources trace it to an identical Old French word, borrowed into English phonetically as shagreen, meaning ‘rough skin or hide’ (the connecting notion being ‘roughness, harshness’), which is itself of uncertain origin. The modern sense of ‘feeling of irritation from disappointment, mortification or mental pain from the failure of aims or plans’ is from 1716” (ibid.).

We may think of linguistics as the scientific study of language, but scientific does not mean that everything that is known is known absolutely. There are lots of gray areas (or should it be “grey areas”?) that afford linguists the opportunity to argue and do further research. By the way, Gamillscheg refers to the Austrian linguist and “Romanist” Ernst Gamillscheg (1887-1971).

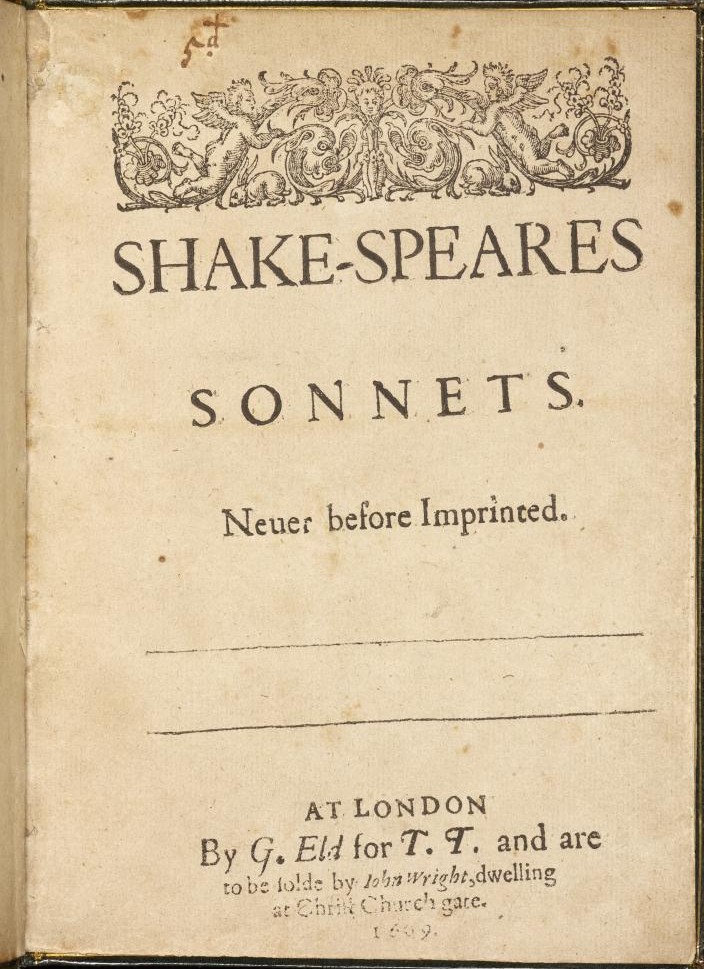

According to On This Day, on this date in 1609, “William Shakespeare’s Sonnets are first published in London, perhaps illicitly, by publisher Thomas Thorpe” (https://www.onthisday.com/events/may/20). Well, that’s sort of true, I think. A Folger Shakespeare Library page says on this date “Thomas Thorpe went to Stationers’ Hall and ‘Entred for his copie vnder th[e h]andes of master WILSON and master Lownes Warden a Booke called SHAKESPEARES sonnettes.’ This first quarto edition appeared later the same year. Given the late date and the seemingly unusual structure of the sequence, some have questioned whether Thorpe might have published the sonnets against Shakespeare’s will; however, most scholars agree that there was nothing illegal or unethical about the book’s publication” (https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/resource/document/sonnets-first-edition).

Shakespeare’s sonnets were probably written in the 1590s and were circulated in manuscript form among friends and associates. The 1590s saw the height of the popularity of the sonnet in England, though sonnet writing goes back to the first half of the 16th century when Sir Thomas Wyatt translated many of Petrarch’s sonnets into English and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, adapted Petrarch’s sonnets into his own. In 1557, Tottel’s Miscellany (actually entitled Songes and Sonnets) reprinted many of the pairs sonnets.

If you are wondering why Shakespeare didn’t just publish the sonnets on his own, it probably has to do with the attitudes of writers in the late 16th century. People were not professional writers; they wrote as part of something else, some other project. Shakespeare may have received some slight compensation for the plays that he wrote, by his primary source of income was as an actor and later as a shareholder in the theater company of which he was part owner. It is true that a couple of his sonnets appeared in a 1599 publication, but there were no copyright laws preventing a publisher from just putting into a miscellany anything that they could get their hands on.

One of the problems with the 1609 publication of Shakespeare’s sonnets by Thorpe is that we have no idea what kind of involvement Shakespeare himself had in the publication. We don’t know if the order of the 154 sonnets is the order in which Shakespeare wrote the sonnets or if they are the order he would have put them in himself. It is possible to determine, from textual clues, that there are small sequences, and the order within those small sequences seem relatively accurate. Also, we have no idea why or to whom the sonnets were written. Perhaps that is a blessing as it has afforded scholars the opportunity to speculate on these issues for over 400 years now. There has been some speculation as to the dedication of the volume, “To W. H.,” but the dedication may have been put there by Thorpe and not Shakespeare, so it may not matter to our understanding of the poet at all.

If someone were to invent a functioning time machine, and if that someone were to go back to the London of 1609, I imagine that that someone would learn three things about the 1609 publication of Shakespeare’s sonnets. The first is that William Shakespeare was a real person and a genius, and that he really did write the poetry and the plays that are credited to him. There is just way too much evidence in favor of the Stratfordian hypothesis, and the theories about others writing the plays are ultimately based on an elitist mindset, as if a middle-class boy could never grow up to be a genius.

The second is that Shakespeare had nothing to do with the 1609 publication of his sonnets.

And the third is that when Thorpe’s publication of Shakespeare’s sonnets came out later that year, it was to Shakespeare’s chagrin.

Today’s image is the title page of Thorpe’s 1609 publication of Shakespeare’s Sonnets (https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/file/special-collections-10739-title-page).