Word of the Day: Gloss

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Merriam-Webster, is gloss. The dictionary gives a definition of the verb: “To gloss a word or phrase is to provide its meaning, or in other words, to explain or define it” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-of-the-day). But under that, M-W explains, “The noun gloss, it follows, refers to (among other things) a brief explanation of a word or expression. And a glossary of course is a collection of textual glosses, or of specialized terms, with their meanings.”

But there are other definitions for the word gloss as well, and the differences, as with so many polysemous words in English, relate to the word’s etymology. The first definition on the etymology page is “’glistening smoothness, luster,”’ 1530s, probably from Scandinavian (compare Icelandic glossi ‘a spark, a flame,’ related to glossa ‘to flame’), or obsolete Dutch gloos ‘a glowing,’ from Middle High German glos; probably ultimately from the same source as English glow (v.). Superficial lustrous smoothness due to the nature of the material (unlike polish, which is artificial)” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=gloss).

The second entry for gloss is the noun version of the definition used by M-W: “’word inserted as an explanation, translation, or definition,’ c. 1300, glose (modern form from 1540s; earlier also gloze), from Late Latin glossa ‘obsolete or foreign word,’ one that requires explanation; later extended to the explanation itself, from Greek glōssa (Ionic), glōtta (Attic) ‘language, a tongue; word of mouth, hearsay,’ also ‘obscure or foreign word, language,’ also ‘mouthpiece,’ literally ‘the tongue’ (as the organ of speech), from PIE *glogh- ‘thorn, point, that which is projected’ (source also of Old Church Slavonic glogu ‘thorn,’ Greek glokhis ‘barb of an arrow’).

“Glosses were common in the Middle Ages, usually rendering Hebrew, Greek, or Latin words into vernacular Germanic, Celtic, or Romanic. Originally written between the lines, later in the margins. By early 14c. in a bad sense, ‘deceitful explanation, commentary that disguises or shifts meaning.’ This sense probably has been colored by gloss (n.1).”

The verb form of gloss enters the language “c. 1300, glosen ‘use fair words; speak smoothly, cajole, flatter;’ late 14c. as ‘comment on (a text), insert a word as an explanation, interpret,’ from Medieval Latin glossare and Old French gloser, from Late Latin glossa (see gloss (n.2)). Modern spelling from 16c.; formerly also gloze.”

So one gloss comes from German, and the other gloss comes from Latin, though there may be an influence of one upon the other.

On this date in 1386, England’s King Richard III and Portugal’s King John I of Portugal ratified an alliance that is now the longest current treaty of its kind. It is still in effect today, 639 years later. And it was actually agreed upon 13 years earlier.

The alliance was born of pragmatism. In 1369, France cemented an alliance with the Kingdom of Castille (https://history.blog.gov.uk/2016/05/09/historys-unparalleled-alliance-the-anglo-portuguese-treaty-of-windsor-9th-may-1386/). Castille was the kingdom the comprised the center of the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula, the country that would later combine with Aragon, and eventually take over the entire Iberian Peninsula except for the western-most part, which is still Portugal. This alliance threatened both Portugal and England.

Castille tried to take over the entire peninsula frequently during the Middle Ages, and that meant taking control of Portugal. There was the Portuguese-Castillian War of 1250-1253 and the Fernandine Wars, which took place 1369–70, 1372–73, and 1381–82, although the latter were instigated more by Ferdinand I of Portugal than by Castille. Still, Castille was a constant threat to Portugal.

France and England were at odds, too. The struggle between the French and the English in a sense dated from 1066, when the Norman French conquered England. The English kings owned large parts of France at various times in the Middle Ages, which led to an unusual situation given the feudal nature of both countries. These English kings were, in a sense, vassals of the French kings. There were 10 Anglo-French Wars between 1109 and 1243. There were four more between 1294 and 1500, one of which was the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453); that war is sometimes divided into three smaller wars, one of which, the Caroline War, lasted from 1369 to 1389, covering the time period of the alliance we’re talking about.

The alliance was not merely military but also a trade alliance. However, it did not prevent the British and the Portuguese from being rivals in the colonization of much of Africa and the Far East. You can learn more about the alliance, such as why Portugal’s neutrality during WWII was actually a benefit to England and the Allies, here: https://britishonlinearchives.com/posts/category/notable-days/628/650-years-the-anglo-portuguese-alliance-between-england-and-portugal.

It’s odd that we never studied the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance in school. Maybe that is because the wars fought by Portugal were never all that important in history, though they were undoubtedly important to the mothers and children of Portuguese and English soldiers who died in those wars, not to mention those on the other side. But perhaps the very alliance between the two nations reduced the impact of such wars; I hope that explains the omittance from history books.

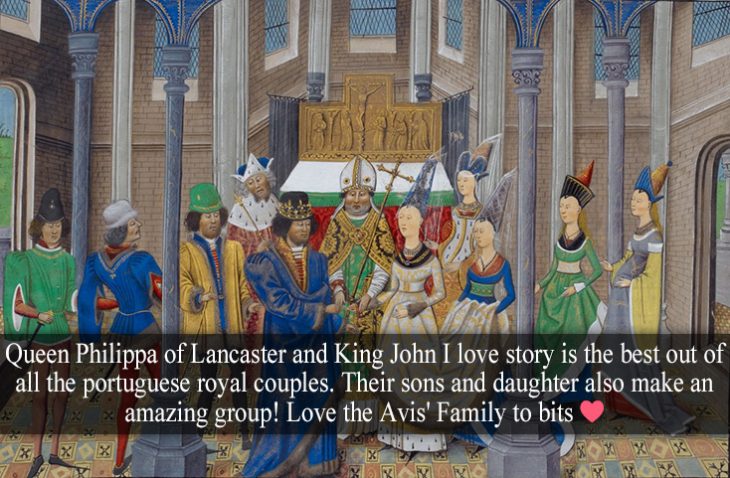

We also never studied the historic marriage between King John I of Portugal and Philippa of Lancaster on Valentine’s Day in 1387, the year after the treaty was ratified. Philippa, the oldest daughter of John of Gaunt, First Duke of Lancaster (well known for a famous speech about England in Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Richard II), was the Queen of Portugal from 1387 until 1415 and bore several children, who came to be known as the Illustrious Generation in Portugal (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippa_of_Lancaster). It was, apparently, one instance when a political marriage worked out.

Today’s image is a painting of the marriage of John I and Philippa from https://royal-confessions.tumblr.com/post/728813569585627137/queen-philippa-of-lancaster-and-king-john-i-love. Perhaps their love story needs an HBO miniseries to fully gloss it.